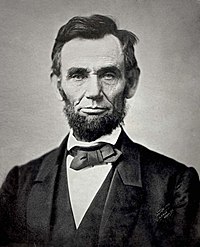

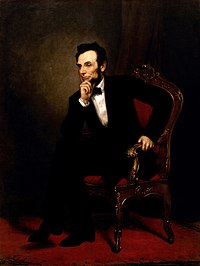

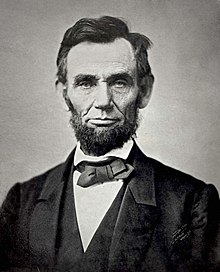

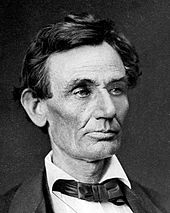

Abraham Lincoln năm 1863 (54 tuổi)

Nhiệm kỳ 4 tháng 3, 1861 – 15 tháng 4,1865

Tiền nhiệm James Buchanan

Kế nhiệm Andrew Johnson

Tiền nhiệm John Henry

Kế nhiệm Thomas Harris

Đảng Cộng hòa (1854–1865)

Liên hiệp Quốc gia (1864–1865)

Sinh 12 tháng 2, 1809

Mất 15 tháng 4, 1865 (56 tuổi)

Washington, D.C., Hoa Kỳ.

Học vấn tự học

Nghề nghiệp Luật sư, Chính trị gia

Tôn giáo Xem Abraham Lincoln và tôn giáo

Phu nhân Mary Todd

Con cái Robert

Abraham Lincoln /ˈeɪbrəhæm ˈlɪŋkən/ (12 tháng 2, 1809 – 15 tháng 4, 1865), còn được biết đến với tên Abe Lincoln, tên hiệu Honest Abe,Rail Splitter, Người giải phóng vĩ đại, là Tổng thống thứ 16 của Hoa Kỳ từ tháng 3 năm 1861 cho đến khi bị ám sát vào tháng 4 năm 1865. Ông được xem là một nhân vật lịch sử tiêu biểu hàng đầu của Hiệp Chủng quốc Hoa Kỳ[1], với tài nghệ chính trị tầm cỡ George Washington.[2]

Lincoln thành công trong nỗ lực lãnh đạo đất nước vượt qua cuộc khủng hoảng hiến pháp, quân sự, và đạo đức – cuộc Nội chiến Mỹ – duy trì chính quyền Liên bang, đồng thời chấm dứt chế độ nô lệ, và hiện đại hóa nền kinh tế, tài chính của đất nước. Sinh trưởng trong một gia đình nghèo ở vùng biên thùy phía Tây, kiến thức Lincoln thu đạt được hầu hết là nhờ tự học. Ông trở thành luật sư nông thôn, nghị viên Viện Lập pháp tiểu bang Illinois, nghị sĩ một nhiệm kỳ ở Viện Dân biểu Hoa Kỳ, rồi trải qua hai lần thất bại trong nỗ lực giành một ghế tại Thượng viện.

Bày tỏ lập trường chống đối chế độ nô lệ tại Hoa Kỳ qua những bài diễn văn và các cuộc tranh luận trong chiến dịch tranh cử,[3] Lincoln nhận được sự đề cử của Đảng Cộng hòa ra tranh cử Tổng thống năm 1860. Sau khi các tiểu bang chủ trương nô lệ ở miền Nam tuyên bố rút khỏiLiên bang Hoa Kỳ, chiến tranh bùng nổ ngày 12 tháng 4, 1861, Lincoln tập trung nỗ lực vào hai phương diện quân sự và chính trị nhằm tái thống nhất đất nước. Ông mạnh dạn hành xử quyền lực trong thời chiến chưa từng có, trong đó có việc bắt giữ và cầm tù không qua xét xử hàng chục ngàn người bị nghi là những kẻ ly khai. Ông ngăn cản Anh Quốc công nhận Liên minh bằng những hành xử khôn ngoan trong sự kiện Trent liên quan đến quan hệ ngoại giao giữa Anh và Hoa Kỳ xảy ra cuối năm 1861. Năm 1861, Lincoln công bố Tuyên ngôn Giải phóng Nô lệ và vận động thông qua Tu chính án thứ Mười ba nhằm bãi bỏ chế độ nô lệ.

Lincoln luôn theo sát diễn biến cuộc chiến, nhất là trong việc tuyển chọn các tướng lĩnh, trong đó có tướng Ulysses S. Grant. Các sử gia đã kết luận rằng Lincoln rất khéo léo giải quyết các chia rẽ trong Đảng Cộng Hòa, ông mời lãnh đạo các nhóm khác nhau trong đảng tham gia nội các và buộc họ phải hợp tác với nhau. Dưới quyền lãnh đạo của ông, Liên bang mở một cuộc phong tỏa hải quân cắt đứt mọi giao thương đến miền Nam, nắm quyền kiểm soát biên giới ngay từ lúc cuộc chiến mới bùng nổ, sử dụng chiến thuyền kiểm soát lưu thông trên hệ thống sông ngòi miền Nam, và nhiều lần cố chiếm thủ đô Liên minh tại Richmond. Mỗi khi có một tướng lĩnh thất trận, ông liền bổ nhiệm một tướng lĩnh khác thay thế cho đến lúc Tướng Grant đạt đến chiến thắng sau cùng năm 1865. Là một chính trị gia sắc sảo từng can thiệp sâu vào các vấn đề quyền lực tại mỗi tiểu bang, ông tạo lập mối quan hệ tốt với nhóm đảng viên Dân chủ ủng hộ cuộc nội chiến, và tái đắc cử trong cuộc bầu cử tổng thống năm 1864.

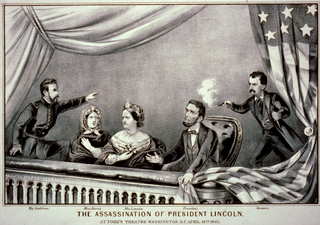

Là lãnh tụ nhóm ôn hòa trong đảng Cộng hòa, Lincoln bị “công kích từ mọi phía”: Đảng viên Cộng hòa cấp tiến đòi hỏi những biện pháp cứng rắn hơn đối với miền Nam, nhóm Dân chủ ủng hộ chiến tranh thì muốn thỏa hiệp, đảng viên Dân chủ chống chiến tranh khinh miệt ông, trong khi những người ly khai cực đoan tìm cách ám sát ông.[4] Trên mặt trận chính trị, Lincoln tự tin đánh trả bằng cách khiến các đối thủ của ông đối đầu với nhau, cùng lúc ông sử dụng tài hùng biện để thuyết phục dân chúng.[5] Diễn văn Gettysburg năm 1863 là bài diễn từ được trích dẫn nhiều nhất trong lịch sử Mỹ Quốc.[6] Đó là bản tuyên ngôn tiêu biểu của tinh thần Mỹ hiến mình cho các nguyên lý cao cả của tinh thần dân tộc, quyền bình đẳng, tự do, và dân chủ. Sau khi chiến tranh kết thúc, Lincoln chủ trương một quan điểm ôn hòa nhằm tái thiết và nhanh chóng tái thống nhất đất nước thông qua chính sách hòa giải và bao dung trong một bối cảnh phân hóa đầy cay đắng với hệ quả kéo dài. Tuy nhiên, chỉ sáu ngày sau khi Tướng Robert E. Lee của Liên minh miền Nam tuyên bố đầu hàng, Lincoln bị ám sát bởi một diễn viên và là người ủng hộ Liên minh, John Wilkes Booth, tại Hí viện Ford khi ông đang xem vở kịch ‘’Our American Cousin’’. Đây là lần đầu tiên một tổng thống Hoa Kỳ bị ám sát. Dẫu có nhiều ý kiến mâu thuẫn về ông,[7] Lincoln liên tục được xếp vào danh sách ba vị tổng thống vĩ đại nhất của nước Mỹ,[8] và được xem là một chính khách mẫu mực đại diện cho mọi phẩm chất tốt đẹp của nền Dân chủ Cộng hòa tại Hoa Kỳ,[9] với tinh thần bình đẳng và quên mình vì nước.[10]

Gia cảnh và tuổi thơ

Thiếu thời

|

|

|

Abraham Lincoln chào đời ngày 12 tháng 2, 1809 (cùng ngày sinh với Charles Darwin), là con thứ hai của Thomas Lincoln và Nancy Lincoln (nhũ danh Hanks), trong một căn nhà gỗ một phòng ở Nông trại Sinking Spring thuộc Hạt Hardin, Kentucky rộng 348 acre (1.4 km²) ở phía đông nam Quận Hardin, Kentucky, khi ấy còn bị coi là biên giới (nay là một phần của Quận LaRue, ở Nolin Creek, cách Hodgenville 3 dặm (5 km).[11] Cậu được đặt theo tên của ông nội, người đã dời gia đình từ Virginia đến Hạt Jefferson, Kentucky,[12][13] tại đó ông bị thiệt mạng trong một trận phục kích của người da đỏ năm 1786 trước sự chứng kiến của các con, trong đó có thân phụ của Lincoln, Thomas.[13] Sau đó, Thomas một mình tìm đường đến khu biên thùy.[14] Mẹ của Lincoln, Nancy, là con gái của Lucy Hanks, sinh tại một địa điểm nay là Hạt Mineral, West Virginia, khi ấy thuộc bang Virginia. Lucy đem Nancy đến Kentucky. Nancy Hanks kết hôn với Thomas, lúc ấy Thomas đã là một công dân khả kính trong cộng đồng. Gia đình gia nhập một nhà thờ Baptist chủ trương tuân thủ nghiêm nhặt các chuẩn mực đạo đức, chống đối việc uống rượu, khiêu vũ, và chế độ nô lệ.[15]

Cha mẹ Lincoln là những nông dân thất học và mù chữ. Khi Lincoln đã trở nên nổi tiếng, những nhà báo và những người viết truyện đã thổi phồng sự nghèo khổ và tối tăm của ông khi ra đời. Tuy nhiên, Thomas Lincoln là một công dân khá có ảnh hưởng ở vùng nông thôn Kentucky. Ông đã mua lại Trang trại Sinking Spring vào tháng 12 năm 1808 với giá $200 tiền mặt và một khoản nợ. Trang trại này hiện được bảo tồn như một phần của Địa điểm di tích lịch sử quốc gia nơi sinh Abraham Lincoln. Thomas được chọn vào bồi thẩm đoàn, và được mời thẩm định giá trị các điền trang. Vào thời điểm con trai của ông Abraham chào đời, Thomas sở hữu hai nông trang rộng 600 mẫu Anh (240 ha), vài khu đất trong thị trấn, bầy gia súc và ngựa. Ông ở trong số những người giàu có nhất trong hạt.[12][16] Tuy nhiên, đến năm Thomas bị mất hết đất đai trong một vụ án vì sai sót trong việc thiết lập chủ quyền điền thổ.

Ba năm sau khi mua trang trại, một người chủ đất trước đó đưa hồ sơ ra trước Toà án Hardin Circuit buộc gia đình Lincoln phải chuyển đi. Thomas theo đuổi vụ kiện cho tới khi ông bị xử thua năm 1815. Những chi phí kiện tụng khiến gia cảnh càng khó khăn thêm. Năm 1811, họ thuê được 30 acres (0.1 km²) trong trang trại Knob Creek rộng 230 acre (0.9 km²) cách đó vài dặm, nơi họ sẽ chuyển tới sống sau này. Nằm trong lưu vực Sông Rolling Fork, đó là một trong những nơi có đất canh tác tốt nhất vùng. Khi ấy, cha Lincoln là một thành viên được kính trọng trong cộng đồng và là một nông dân cũng như thợ mộc tài giỏi. Hồi ức sớm nhất của Lincoln bắt đầu có ở trang trại này. Năm 1815, một nguyên đơn khác tìm cách buộc gia đình Lincoln phải rời trang trại Knob Creek. Nản chí trước sự kiện tụng cũng như không được các toà án ở Kentucky bảo vệ, Thomas quyết định đi tới Indiana, nơi đã được chính phủ liên bang khảo sát, nên quyền sở hữu đất đai cũng được bảo đảm hơn. Có lẽ những giai đoạn tuổi thơ ấy đã thúc đẩy Abraham theo học trắc địa và trở thành một luật sư.

Gia đình băng qua sông Ohio để dời đến một lãnh thổ không có nô lệ và bắt đầu cuộc sống mới ở Hạt Perry, Indiana. Tại đây, năm 1818 khi Lincoln lên chín, mẹ cậu qua đời.[17] Sarah, chị của Lincoln, chăm sóc cậu cho đến khi ông bố tái hôn năm 1898; về sau Sarah chết ở lứa tuổi 20 trong lúc sinh nở.[18]

Hãy quyết tâm sống chân thật trong mọi sự; nếu bạn thấy mình không thể trở thành một luật sư trung thực, thì hãy cố sống trung thực mà không cần phải làm luật sư.

Abraham Lincoln[19]

Vợ mới của Thomas Lincoln, Sarah Bush Johnston, nguyên là một góa phụ, mẹ của ba con. Lincoln rất gần gũi với mẹ kế, gọi bà là “Mẹ”.[20] Khi còn bé, Lincoln không thích nếp sống lao động cực nhọc ở vùng biên thùy, thường bị người nhà và láng giềng xem là lười biếng.[21][22] Nhưng khi đến tuổi thiếu niên, cậu tình nguyện đảm trách tất cả việc nhà, trở thành một người sử dụng rìu thành thục khi xây dựng hàng rào. Cậu cũng được biết tiếng nhờ sức mạnh cơ bắp và tính gan lì sau một trận đấu vật quyết liệt với thủ lĩnh một nhóm côn đồ gọi là "the Clary's Grove boys".[23] Cậu cũng tuân giữ tập tục giao hết cho cha toàn bộ lợi tức cậu kiếm được cho đến tuổi 21.[17] Giáo dục tiểu học cậu bé Lincoln tiếp nhận chỉ tương đương một năm học do các giáo viên lưu động giảng dạy, hầu hết là do cậu tự học và tích cực đọc sách.[24] Trên thực tế Linoln là người tự học, đọc mọi cuốn sách có thể mượn được. Cậu thông thạo Kinh Thánh, các tác phẩm của William Shakespeare, lịch sử Anh, lịch sử Mỹ, và học được phong cách trình bày giản dị trước thính giả. Lincoln không thích câu cá và săn bắn vì không muốn giết hại bất cứ một con vật nào kể cả để làm thực phẩm dù cậu rất cao và khoẻ, cậu dành nhiều thời gian đọc sách tới nỗi những người hàng xóm cho rằng cậu cố tình làm vậy để tránh phải làm việc chân tay nặng nhọc.

Năm 1830, để tránh căn bệnh nhiễm độc sữa mới vừa bùng nổ dọc theo sông Ohio, gia đình Lincoln di chuyển về hướng tây và định cư trên khu đất công ở Hạt Macon, Illinois, một tiểu bang không có nô lệ.[25] Năm 1831, Thomas đem gia đình đến Hạt Coles, Illinois. Lúc ấy, là một thanh niên đầy khát vọng ở tuổi 22, Lincoln quyết định rời bỏ gia đình để tìm kiếm một cuộc sống tốt hơn. Cậu đi xuồng xuôi dòng Sangamon đến làng New Salem thuộc Hạt Sangamon.[26] Mùa xuân năm 1831, sau khi thuê mướn Lincoln, Denton Offutt, một thương nhân ở New Salem, cùng một nhóm bạn, vận chuyển hàng hóa bằng xà lan từ New Salem theo sông Sangamon và Mississippi đến New Orleans. Tại đây, lần đầu tiên chứng kiến tận mắt tệ nạn nô lệ, Lincoln đi bộ trở về nhà.[27]

Trong một tự truyện, Lincoln miêu tả mình trong giai đoạn này - ở lứa tuổi 20, rời bỏ vùng rừng núi hẻo lánh để tìm đường tiến vào thế giới – như là “một gã trai kỳ dị, không bạn bè, không học thức, không một xu dính túi”.[28]

Hôn nhân và con cái

|

| Tổng thống Lincoln cùng cậu con út, Tad, năm 1864 |

Năm 1840, Lincoln đính hôn với Mary Todd, con gái của một gia đình giàu có sở hữu nô lệ ở Lexington, Kentucky.[29] Họ gặp nhau lần đầu ở Springfield, Illinois vào tháng 12 năm 1839,[30] rồi đính hôn vào tháng 12 năm sau.[31] Hôn lễ được sắp đặt vào ngày 1 tháng 1, 1841, nhưng bị Lincoln đề nghị hủy bỏ.[30][32] Sau này họ lại gặp nhau và kết hôn ngày 4 tháng 11, 1842, hôn lễ tổ chức tại ngôi biệt thự của người chị của Mary ở Springfield.[33] Ngay cả khi đang chuẩn bị cho hôn lễ, Lincoln vẫn cảm thấy lưỡng lự. Khi được hỏi cuộc hôn nhân này sẽ dẫn ông đến đâu, Lincoln trả lời, “Địa ngục, tôi nghĩ thế.”[34] Năm 1844, hai người mua một ngôi nhà ở Springfield gần văn phòng luật của Lincoln.[35] Mary Todd Lincoln là người vợ đảm đang, chu tất việc nội trợ như đã từng làm khi còn sống với cha mẹ ở Kentucky. Cô cũng giỏi vén khéo với đồng lương ít ỏi chồng cô kiếm được khi hành nghề luật.[36] Robert Todd Lincoln chào đời năm 1843, kế đó là Edward (Eddie) trong năm 1846. Lincoln “đặc biệt yêu thích lũ trẻ”,[37] và thường tỏ ra dễ dãi với chúng.[38] Robert là người con duy nhất còn sống cho đến tuổi trưởng thành. Edward mất ngày 1 tháng 1, 1850 ở Springfield do lao phổi. “Wille” Lincoln sinh ngày 21 tháng 12, 1850 và mất ngày 20 tháng 2, 1862. Đứa con thứ tư của Lincoln, “Tad” Lincoln, sinh ngày 4 tháng 4, 1853, và chết vì mắc bệnh tim ở tuổi 18 (16 tháng 7, 1871).[39]

Cái chết của những cậu con trai đã tác động mạnh trên cha mẹ chúng. Cuối đời, Mary mắc chứng u uất do mất chồng và các con, có lúc Robert Todd Lincoln phải gởi mẹ vào viện tâm thần trong năm 1875.[40] Abraham Lincoln thường khi vẫn “u sầu, phiền muộn”, ngày nay được coi là triệu chứng của bệnh trầm cảm.[41]

Robert có ba con và ba cháu. Không một ai trong số cháu của ông có con, vì thế dòng dõi Lincoln chấm dứt khi Robert Beckwith (cháu trai của Lincoln) chết ngày 24 tháng 12, 1985.[1]

[sửa]Khởi nghiệp

Năm 1832, ở tuổi 23, Lincoln cùng một đối tác mua chịu một cửa hàng tạp hóa ở New Salem, Illinois. Mặc dù kinh tế trong vùng đang phát triển, doanh nghiệp của họ phải vất vả để tồn tại, cuối cùng Lincoln phải sang nhượng cổ phần của ông. Tháng 3 năm ấy, Lincoln bắt đầu sự nghiệp chính trị bằng cách tranh cử vào Nghị viện Illinois. Ông giành được thiện cảm của dân địa phương, thu hút nhiều đám đông ở New Salem bằng biệt tài kể chuyện đầy hóm hỉnh, mặc dù ông thiếu học thức, thân hữu có thế lực, và tiền bạc, là những yếu tố có thể khiến ông thất cử. Khi tranh cử, ông chủ trương cải thiện lưu thông đường thủy trên sông Sangamon.[42]

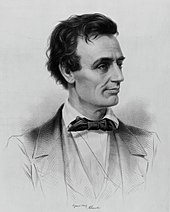

|

Bức phác họa chân dung ứng cử viên Abraham Lincoln Bức phác họa chân dung ứng cử viên Abraham Lincoln |

Trước cuộc bầu cử, Lincoln phục vụ trong lực lượng dân quân Illinois với cấp bậc đại úy suốt trong Chiến tranh Black Hawk (một cuộc chiến ngắn ngủi chống lại người da đỏ).[43] Sau chiến tranh, ông trở lại vận động cho cuộc bầu cử ngày 6 tháng 8 vào Nghị viện Illinois. Với chiều cao 6 foot 4 inch (193 cm),[44]Lincoln cao và “đủ mạnh để đe dọa bất kỳ đối thủ nào.” Ngay từ lần diễn thuyết đầu tiên, khi nhìn thấy một người ủng hộ ông trong đám đông bị tấn công, Lincoln liền đến “túm cổ và đáy quần gã kia” rồi ném hắn ra xa.[45] Lincoln về hạng tám trong số mười ba ứng cử viên (chỉ bốn người đứng đầu được đắc cử).[46]

Lincoln quay sang làm trưởng bưu điện New Salem, rồi đo đạc địa chính; suốt thời gian ấy ông vẫn say mê đọc sách. Cuối cùng ông quyết định trở thành luật sư, bắt đầu tự học bằng cách nghiền ngẫm quyển Commentaries on the Laws of England của Blackstone, và những sách luật khác. Về phương pháp học, Lincoln tự nhận xét về mình: “Tôi chẳng học ai hết.”[47] Lincoln thành công khi ra tranh cử lần thứ hai năm 1834. Ông vào viện lập pháp tiểu bang. Sau khi được nhận vào Đoàn Luật sư Hoa Kỳ năm 1836,[48] ông dời đến Springfield, Illinois bắt đầu hành nghề luật dưới sự dẫn dắt của John T. Stuart, một người anh em họ của Mary Todd.[49] Dần dà, Lincoln trở thành một luật sư tài năng và thành đạt. Từ năm 1841 đến 1844, ông cộng tác với Stephen T. Logan, rồi với William Herndon, ông đánh giá Herndon là “một thanh niên chuyên cần”.

Năm 1841, Lincoln hành nghề luật cùng William Herndon, một người bạn trong Đảng Whig. Năm 1856, hai người tham gia Đảng Cộng hoà. Sau khi Lincoln chết, Herndon bắt đầu sưu tập các câu chuyện về Lincoln từ những người từng biết ông ở Illinois, và xuất bản chúng trong cuốn Lincoln của Herndon.

Trong kỳ họp 1835-1836, ông bỏ phiếu ủng hộ chủ trương mở rộng quyền bầu cử cho nam giới da trắng, dù có sở hữu đất đai hay không.[50] Ông nổi tiếng với lập trường "free soil" chống chế độ nô lệ lẫn chủ trương bãi bỏ nô lệ. Lần đầu tiên trình bày về chủ đề này trong năm 1837, ông nói, “Định chế nô lệ được thiết lập trên sự bất công và chính sách sai lầm, nhưng tuyên bố bãi nô chỉ làm gia tăng thay vì giảm thiểu tội ác này.”[51] Ông theo sát Henry Clay trong nỗ lực ủng hộ việc trợ giúp những nô lệ được tự do đến định cư tại Liberia ở châu Phi.[52] Ông phục vụ bốn nhiệm kỳ liên tiếp ở Viện Dân biểu tiểu bang Illinois, đại diện cho Hạt Sangamon.[53]

[sửa]Vị Tổng thống đầu tiên của nước Mỹ có bằng sáng chế

Trên thực tế nhiều người xem vị tổng thống thứ 3 của nước Mỹ, Thomas Jefferson là nhà phát minh vĩ đại nhất từng sống ở Nhà Trắng. Nhưng vị Tổng thống này chưa bao giờ lấy bằng sáng chếcho những ý tưởng của mình. Trong lịch sử nước Mỹ, chỉ duy nhất một Tổng thống từng được cấp bằng sáng chế cho dù bình thường ông ít quan tâm đến công nghệ, đó là Tổng thống Abraham Lincoln.

Vào cuối những năm 1890, Lincoln là đại biểu Quốc hội của bang Illinois. Ông thường đi lại giữa Washington và Illinois trên con tàu chạy bằng hơi nước Great Lakes. Một lần tàu bị mắt kẹt ở bãi cát ngay giữa sông. Tât cả hành khách và hàng hoá phải chuyển đi để con tàu nổi dần lên. Đó là một quá trình dài và buồn tẻ.

Điều này mang đến cho Lincoln một ý tưởng, khi trở về văn phòng luật sư của mình ở Illinois, ông bắt đầu sáng chế ra một thiết bị có thể làm con tàu nổi lên mà không cần phải làm cho nó nhẹ đi bằng việc bóc dở hàng hoá xuống. Ông tranh thủ gọt đẽo mô hình giữa các phiên toà. Kết quả, ông nhận được bằng sáng chế số 6469: "Cách làm nổi những con tàu lớn".

Phát minh của Lincoln được chứng minh là không thực tế và không được đưa vào sản xuất. Nhưng nó đã cho thấy vị luật sư có tài xoay xở này sở hữu một trí tuệ đầy sáng tạo và dám thực hiện những ý tưởng mới. Đó là ý chí mà nước Mỹ rất cần trong những năm tháng bất ổn sau này.

[sửa]Nghị trường Liên bang

|

Lincoln, năm 1846 Lincoln, năm 1846 |

Từ đầu thập niên 1930, Lincoln là thành viên kiên trung của đảng Whig, tự nhận mình là “một đảng viên Whig bảo thủ, một môn đệ của Henry Clay”.[54] Đảng Whig ủng hộ hiện đại hóa nền kinh tế trong các lĩnh vực ngân hàng, dùng thuế bảo hộ để cung ứng ngân sách cho phát triển nội địa như đường sắt, và tán thành chủ trương đô thị hóa.[55]

Năm 1846, Lincoln đắc cử vào Viện Dân biểu Hoa Kỳ, phục vụ một nhiệm kỳ hai năm. Ông là đảng viên Whig duy nhất trong đoàn đại biểu đến từ Illinois, ông sốt sắng bày tỏ lòng trung thành với đảng của mình trong các cuộc biểu quyết và phát biểu ủng hộ chủ trương của đảng.[56] Cộng tác với Joshua R. Giddings, một dân biểu chủ trương bãi nô, Lincoln soạn thảo một dự luật nhằm bãi bỏ chế độ nô lệ tại Hạt Columbia, nhưng ông phải từ bỏ ý định vì không có đủ hậu thuẫn từ trong đảng Whig.[57] Về chính sách ngoại giao và quân sự, Lincoln lớn tiếng chống cuộc chiến Mễ-Mỹ, chỉ trích Tổng thống James K. Polk là chỉ lo tìm kiếm “thanh danh về quân sự - một ảo vọng nhuốm máu”.[58]

Bằng cách soạn thảo và đệ trình Nghị quyết Spot, Linconln quyết liệt bác bỏ quan điểm của Polk. Cuộc chiến khởi phát do người Mexico sát hại binh sĩ Mỹ ở vùng lãnh thổ đang tranh chấp giữa Mexico và Hoa Kỳ; Polk nhấn mạnh rằng binh sĩ Mexico đã “xâm lăng lãnh thổ chúng ta” và làm đổ máu đồng bào chúng ta ngay trên “đất của chúng ta”.[59][60] Lincoln yêu cầu Polk trình bày trước Quốc hội địa điểm chính xác nơi máu đã đổ và chứng minh địa điểm đó thuộc về nước Mỹ.[60] Quốc hội không chịu thảo luận về nghị quyết, báo chí trong nước phớt lờ nó, và Lincoln bị mất hậu thuẫn chính trị ngay tại khu vực bầu cử của ông. Một tờ báo ở Illinois gán cho ông biệt danh “spotty Lincoln”.[61][62][63] Về sau, Lincoln tỏ ra hối tiếc về một số phát biểu của ông, nhất là khi ông tấn công quyền tuyên chiến của tổng thống.[64]

Nhận thấy rằng Clay không thể thắng cử, Lincoln, năm 1846 đã cam kết chỉ phục vụ một nhiệm kỳ tại Viện Dân biểu, ủng hộ Tướng Zachary Taylor đại diện đảng Whig trong cuộc đua năm 1848 tranh chức tổng thống.[65] Khi Taylor đắc cử, Lincoln hi vọng được bổ nhiệm lãnh đạo Tổng Cục Địa chính (General Land Office), nhưng chức vụ béo bở này lại về tay một đối thủ của ông, Justin Butterfield, người được chính phủ đánh giá là một luật sư lão luyện, nhưng theo Lincoln, Butterfield chỉ là một “tảng hóa thạch cổ lỗ”.[66] Chính phủ cho ông giải khuyến khích là chức thống đốc Lãnh thổ Oregon. Vùng đất xa xôi này là căn cứ địa của đảng Dân chủ, chấp nhận nó đồng nghĩa với việc chấm dứt sự nghiệp chính trị và luật pháp của ông ở Illinois, Lincoln từ chối và quay trở lại nghề luật.[67]

[sửa]Luật sư vùng Thảo nguyên

Đừng ham đáo tụng đình. Cố mà hòa giải với hàng xóm. Hãy cho họ thấy thường khi người thắng cuộc thật ra chỉ là kẻ thua đau – mất thời gian mà còn hao tốn tiền của.

Abraham Lincoln.[68]

Lincoln trở lại hành nghề luật ở Springfield, xử lý “mọi loại công việc dành cho luật sư vùng thảo nguyên”.[69] Hai lần mỗi năm trong suốt mười sáu năm, mỗi lần kéo dài hai tuần, ông phải có mặt tại quận lỵ nơi tòa án quận có phiên xét xử.[70] Lincoln giải quyết nhiều vụ tranh chấp trong lĩnh vực giao thông ở miền Tây đang mở rộng, nhất là việc điều vận xà lan sông qua gầm cầu đường hỏa xa mới được xây dựng. Lúc đầu, Lincoln chỉ nhận những vụ ông thích, về sau ông làm việc cho bất cứ ai chịu thuê mướn ông.[71]

Ông dần được biết tiếng, và bắt đầu xuất hiện trước Tối cao Pháp viện Hoa Kỳ, tranh luận trong một vụ án liên quan đến một chiếc thuyền bị chìm do va chạm cầu.[71] Năm 1849, ông được cấp bằng sáng chế về phương tiện đường thủy ứng dụng cho việc lưu thông thuyền trên dòng nước cạn. Dù ý tưởng này chưa từng được thương mại hóa, Lincoln là vị tổng thống duy nhất từng được cấp bằng sáng chế.[72][73]

Lincoln xuất hiện trước Tòa án Tối cao bang Illinois trong 175 vụ án, 51 vụ ông là luật sư biện hộ duy nhất cho thân chủ, trong đó có 31 phán quyết của tòa có lợi cho ông.[74]

Vụ án hình sự nổi bật nhất của Lincoln xảy ra năm 1858 khi ông biện hộ cho William “Duff” Armstrong, bị xét xử vì tội danh sát hại James Preston Metzker.[75] Vụ án nổi tiếng do Lincoln sử dụng một sự kiện hiển nhiên để thách thức sự khả tín của một nhân chứng. Sau khi một nhân chứng khai trước tòa rằng đã chứng kiến vụ án diễn ra dưới ánh trăng, Lincoln rút quyển Niên lịch cho nhà nông, chỉ ra rằng vào thời điểm ấy mặt trăng còn thấp nên giảm thiểu đáng kể tầm nhìn. Dựa trên chứng cứ ấy, Armstrong được tha bổng.[75] Hiếm khi Lincoln phản đối trước tòa; nhưng trong một vụ án năm 1859, khi biện hộ cho Peachy Harrison, một người anh em họ, bị cáo buộc đâm chết người, Lincoln giận dữ phản đối quyết định của thẩm phán bác bỏ một chứng cứ có lợi cho thân chủ của ông. Thay vì buộc tội Lincoln xúc phạm quan tòa, thẩm phán là một đảng viên Dân chủ đã đảo ngược phán quyết của ông, cho phép sử dụng chứng cứ và tha bổng Harrison.[75][76]

Đảng Cộng hòa 1854 – 1860

"Một nhà tự chia rẽ"

Bài chi tiết: Một nhà tự chia rẽ

Trong thập niên 1850, chế độ nô lệ được xem là hợp pháp tại các tiểu bang miền Nam trong khi ở tiểu bang miền Bắc như Illniois nó bị đặt ngoài vòng pháp luật.[77] Lincoln chống chế độ nô lệ và việc mở rộng chế độ nô lệ đến những vùng lãnh thổ mới ở miền Tây.[78] Vì muốn chống đối Đạo luật Kansas-Nebraska (1854) ông đã trở lại chính trường; đạo luật này được thông qua để hủy bỏ Thỏa hiệp Missouri hạn chế chế độ nô lệ. Thượng Nghị sĩ lão thành Stephen A. Douglas của Illinois đã liên kết quyền phổ thông tự quyết vào Đạo luật. Điều khoản của Douglas mà Lincoln bác bỏ là cho những người định cư quyền tự quyết cho địa phương của họ công nhận chế độ nô lệ trong những vùng lãnh thổ mới của Hoa Kỳ.[79]

Foner (2010) phân biệt quan điểm của nhóm chủ trương bãi nô cùng nhóm Cộng hòa cấp tiến ở vùng Đông Bắc là những người xem chế độ nô lệ là tội lỗi, với các đảng viên Cộng hòa bảo thủ chống chế độ nô lệ vì họ nghĩ rằng nó làm tổn thương người da trắng và kìm hãm sự tiến bộ của đất nước. Foner tin rằng Lincoln theo đường lối trung dung, ông phản đối chế độ nô lệ vì nó vi phạm các nguyên lý của chế độ cộng hòa xác lập bởi những nhà lập quốc, nhất là với quyền bình đằng dành cho mọi người và quyền tự quyết lập nền trên các nguyên tắc dân chủ đã được công bố trong bản Tuyên ngôn Độc lập.[80]

Ngày 16 tháng 10, 1854, trong “Diễn văn Peoria”, Lincoln tuyên bố lập trường chống nô lệ dọn đường cho nỗ lực tranh cử tổng thống.[81] Phát biểu với giọng Kentucky, ông nói Đạo luật Kansas “có vẻ vô cảm, song tôi buộc phải nghĩ rằng ẩn chứa trong nó là một sự nhiệt tình thực sự dành cho nỗ lực phổ biến chế độ nô lệ. Tôi không thể làm gì khác hơn là căm ghét nó. Tôi ghét nó bởi vì sự bất công đáng ghê tởm của chế độ nô lệ. Tôi ghét nó bởi vì nó tước đoạt ảnh hưởng công chính của hình mẫu nền cộng hòa của chúng ta đang tác động trên thế giới...”[82]

Tôi không phải là nô lệ, nên tôi không thể là chủ nô. Đó là quan điểm của tôi về dân chủ. Bất cứ cái gì khác với điều này, đều không phải là dân chủ.

Abraham Lincoln[83]

Cuối năm 1854, Lincoln ra tranh cử trong tư cách đảng viên đảng Whig đại diện Illinois tại Thượng viện Hoa Kỳ. Lúc ấy, viện lập pháp tiểu bang được dành quyền bầu chọn thượng nghị sĩ liên bang.[84] Sau khi dẫn đầu trong sáu vòng bầu cử đầu tiên tại nghị viện Illinois, hậu thuẫn dành cho Lincoln suy yếu dần, ông phải kêu gọi những người ủng hộ ông bầu phiếu cho Lyman Trumbull, người đã đánh bại đối thủ Joel Aldrich Matteson.[85] Đạo luật Kansas gây ra sự phân hóa vô phương cứu chữa trong nội bộ đảng Whig. Lôi kéo thành phần còn lại của đảng Whig cùng những người vỡ mộng từ các đảng Free Soil, Tự do, Dân chủ, ông hoạt động tích cực trong nỗ lực hình thành một chính đảng mới, Đảng Cộng hòa.[86] Tại đại hội đảng năm 1856, Lincoln là nhân vật thứ hai trong cuộc đua giành sự đề cử của đảng cho chức vụ phó tổng thống.[87]

Trong khoảng 1857-58, do bất đồng với Tổng thống James Buchanan, Douglas dẫn đầu một cuộc tranh đấu giành quyền kiểm soát Đảng Dân chủ. Một số đảng viên Cộng hòa cũng ủng hộ Douglas trong nỗ lực tái tranh cử vào Thượng viện năm 1858 bởi vì ông chống bản Hiến chương Lecompton xem Kansas là tiểu bang chấp nhận chế độ nô lệ.[88] Tháng 3 năm 1857, khi ban hành phán quyết trong vụ án Dred Scott chống Sandford, Chánh án Roger B. Taney lập luận rằng bởi vì người da đen không phải là công dân, họ không được hưởng bất kỳ quyền gì qui định trong Hiến pháp. Lincoln lên tiếng cáo giác đó là âm mưu của phe Dân chủ, “Các tác giả của bản Tuyên ngôn Độc lập không ‘nói mọi người bình đẳng trong màu da, thể hình, trí tuệ, sự phát triển đạo đức, khả năng xã hội’, song họ ‘thực sự xem mọi người sinh ra đều bình đẳng trong những quyền không thể chuyển nhượng, trong đó có quyền sống, tự do, và mưu cầu hạnh phúc.’”[89]

Sau khi được đại hội bang Đảng Cộng hòa đề cử tranh ghế tại Thượng viện năm 1858, Lincoln đọc bài diễn văn Một nhà tự chia rẽ, gợi ý từ Phúc âm Mác trong Kinh Thánh:

“ ..."Một nhà tự chia rẽ thì nhà ấy không thể đứng vững được". Tôi tin rằng chính quyền này không thể trường tồn trong tình trạng một nửa nước nô lệ, một nửa nước tự do. Tôi không mong chờ chính quyền liên bang bị giải thể - tôi không mong đợi ngôi nhà bị sụp đổ - nhưng tôi thực sự trông mong đất nước này sẽ không còn bị chia rẽ.

Đất nước chúng ta sẽ trở thành một thực thể như thế này hoặc là hoàn toàn khác. Hoặc là những người chống chế độ nô lệ sẽ kìm hãm được tệ nạn này, và khiến công chúng tin rằng cuối cùng nó sẽ không còn tồn tại; hoặc là những người ủng hộ chế độ nô lệ sẽ phát triển và biến nó thành hợp pháp tại mọi tiểu bang, mới cũng như cũ – miền Bắc cũng như miền Nam….[90]. ”

Bài diễn văn đã tạo dựng được một hình ảnh sinh động liên tưởng đến hiểm họa phân hóa đất nước gây ra bởi những bất đồng về chế độ nô lệ, và là lời hiệu triệu tập hợp đảng viên Cộng hòa khắp miền Bắc.[91]

[sửa]Tranh luận giữa Lincoln và Douglas

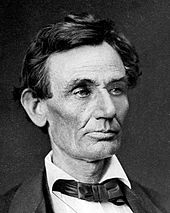

|

Lincoln năm 1860, ảnh A. Hesler. Lincoln năm 1860, ảnh A. Hesler. |

Năm 1858 chứng kiến bảy cuộc tranh luận giữa Lincoln và Douglas khi diễn ra cuộc vận động tranh cử vào Thượng viện, đây là những cuộc tranh luận chính trị nổi tiếng nhất trong lịch sử Hoa Kỳ.[92] Lincoln cảnh báo rằng chế độ nô lệ đang đe dọa những giá trị của chủ thuyết cộng hòa, và cáo buộc Douglas là bẻ cong các giá trị của những nhà lập quốc về nguyên lý mọi người sinh ra đều bình đẳng, trong khi Douglas nhấn mạnh đến quyền tự quyết của cư dân địa phương xem họ có chấp nhận chế độ nô lệ hay không.[93]

Các ứng cử viên Cộng hòa giành nhiều phiếu phổ thông hơn, nhưng những người Dân chủ chiếm được nhiều ghế hơn trong viện lập pháp tiểu bang. Viện Lập pháp đã tái bầu Douglas vào Thượng viện Hoa Kỳ. Dù bị thất bại cay đắng, khả năng hùng biện của Lincoln mang đến cho ông danh tiếng trên chính trường quốc gia.[94]

[sửa]Diễn văn Cooper Union

Ngày 27 tháng 2, 1860, giới lãnh đạo đảng ở New York mời Lincoln đọc diễn văn tại Liên minh Cooper, trước một cử tọa gồm những nhân vật có thế lực trong đảng Cộng hòa. Lincoln lập luận rằng những nhà lập quốc không mấy quan tâm đến quyền tự quyết phổ thông, nhưng thường xuyên tìm cách kìm chế chế độ nô lệ. Ông nhấn mạnh rằng nền tảng đạo đức của người Cộng hòa đòi hỏi họ phải chống lại chế độ nô lệ, và mọi sự “cám dỗ chấp nhận lập trường trung dung giữa lẽ phải và điều sai trái.” [95]

Việc phô bày khả năng lãnh đạo đầy trí tuệ đã đưa Lincoln vào nhóm những chính trị gia hàng đầu của đảng và dọn đường cho ông trong nỗ lực giành sự đề cử của đảng tranh chức tổng thống. Nhà báo Noah Brooks tường thuật, “Chưa từng có ai tạo được ấn tượng mạnh mẽ như thế như lẩn đầu tiên ông hiệu triệu một cử tọa ở New York.” [96][97]Donald miêu tả bài diễn văn là “một động thái chính trị siêu đẳng cho một ứng cử viên chưa tuyên bố tranh cử, xuất hiện ở chính tiểu bang của đối thủ (William H. Seward), ngay tại một sự kiện do những người trung thành với đối thủ thứ hai (Salmon P. Chase) bảo trợ, mà không cần phải nhắc đến tên của họ trong suốt bài diễn văn.[98]

Chiến dịch Tranh cử Tổng thống năm 1860

Đại hội tiểu bang Đảng Cộng hòa tổ chức tại Decatur trong hai ngày 9 và 10 tháng 5, 1860. Lincoln nhận được ủng hộ để ra tranh cử tổng thổng.[99] Ngày 18 tháng 5, tại Đại hội Toàn quốc Đảng Cộng hòa năm 1860, tổ chức ở Chicago, ở vòng bầu phiếu thứ ba, Lincoln giành được sự đề cử, một người từng là đảng viên Dân chủ đến từ Maine, Hannibal Hamlin, được chọn đứng cùng liên danh với ông để tạo thế cân bằng. Thành quả này có được là nhờ danh tiếng của ông như là một chính trị gia có lập trường ôn hòa về vấn đề nô lệ cũng như sự ủng hộ mạnh mẽ của ông dành cho các chương trình của Đảng Whig cải thiện các vấn đề trong nước và bảo hộ hàng nội địa.[100]

Trong suốt thập niên 1850, Lincoln không tin sẽ xảy ra cuộc nội chiến, những người ủng hộ ông cũng bác bỏ việc ông đắc cử sẽ dẫn đến khả năng chia cắt đất nước.[101] Trong lúc ấy, Douglas được chọn làm ứng cử viên cho Đảng Dân chủ. Những đoàn đại biểu từ 11 tiểu bang ủng hộ chế độ nô lệ bỏ phòng họp vì bất đồng với quan điểm của Douglas về quyền tự quyết phổ thông, sau cùng họ chọn John C. Breckinridge làm ứng cử viên.[102]

Lincoln là ứng cử viên duy nhất không đọc diễn văn tranh cử, nhưng ông theo dõi sát sao cuộc vận động và tin cậy vào bầu nhiệt huyết của đảng viên Cộng hòa. Họ di chuyển nhiều và tạo lập những nhóm đa số khắp miền Bắc, in ấn và phổ biến một khối lượng lớn áp-phích, tờ rơi, và viết nhiều bài xã luận trên các nhật báo. Có hàng ngàn thuyết trình viên Cộng hòa quảng bá cương lĩnh đảng và những trải nghiệm sống của Lincoln, nhấn mạnh đến tuổi thơ nghèo khó của ông. Mục tiêu của họ là trình bày sức mạnh vượt trội của quyền lao động tự do, nhờ đó mà một cậu bé quê mùa lớn lên từ nông trại nhờ nỗ lực bản thân mà trở thành một chính trị hàng đầu của xứ sở.[103] Phương pháp quảng bá hiệu quả của Đảng Cộng hòa đã làm suy yếu các đối thủ; một cây bút của tờ Chicago Tribune viết một tiểu luận miêu tả chi tiết cuộc đời Lincoln, bán được khoảng từ 100 đến 200 ngàn ấn bản.[104]

[sửa]Tổng thống

[sửa]Bầu cử năm 1860

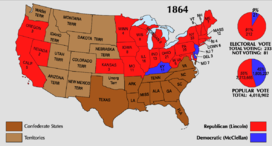

Năm 1860, phiếu bầu của cử tri đoàn phía bắc và phía tây (đỏ) đã giúp Lincoln thắng cử.

|

| Năm 1861, lễ nhậm chức trước Tòa nhà Quốc hội (đang xây dựng) |

Ngày 6 tháng 11, 1860, Lincoln đắc cử để trở thành tổng thống thứ mười sáu của Hoa Kỳ. Ông vượt quaStephen A. Douglas của Đảng Dân chủ, John C. Breckinridge của Đảng Dân chủ miền Nam, và John Bell của Đảng Liên minh Hiến pháp mới được thành lập năm 1860. Lincoln là đảng viên Cộng hòa đầu tiên đảm nhận chức vụ tổng thống. Chiến thắng của ông hoàn toàn dựa trên sự ủng hộ ở miền Bắc và miền Tây. Không có phiếu bầu cho Lincoln tại mười trong số mười lăm tiểu bang miền Nam sở hữu nô lệ; ông chỉ về đầu ở 2 trong số 996 hạt trên tất cả các tiểu bang miền Nam.[105] Lincoln nhận được 1 866 452 phiếu bầu, trong khi Douglas có 1 376 957 phiếu, Breckinridge 849 781 phiếu, và Bell được 588 789 phiếu.

Ly khai

Khi kết quả bầu cử đã rõ ràng, những người chủ trương ly khai nói rõ ý định của họ là sẽ tách khỏi Liên bang trước khi Lincoln nhậm chức vào tháng 3 tới.[106] Ngày 20 tháng 12, 1860, bang South Carolina dẫn đầu bằng cách chấp nhận luật ly khai; ngày 1 tháng 2, 1861, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia,Louisiana, và Texas tiếp bước.[107][108] Sáu trong số các tiểu bang này thông qua một bản hiến pháp, và tuyên bố họ là một quốc gia có chủ quyền, Liên minh miền Nam.[107] Các tiểu bang Delaware, Maryland,Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, và Arkansas có lắng nghe nhưng không chịu ly khai.[109] Tổng thống đương nhiệm Buchanan và Tổng thống tân cử Lincoln từ chối công nhận Liên minh, tuyên bố hành động ly khai là bất hợp pháp.[110] Ngày 9 tháng 2, 1861, Liên minh miền Nam chọn Jefferson Davis làm Tổng thống lâm thời.[111]

Khởi đầu là những nỗ lực hòa giải. Thỏa hiệp Crittenden mở rộng thêm những điều khoản của Thỏa hiệp Missouri năm 1820, phân chia thành các vùng tự do và vùng có nô lệ, điều này trái ngược với cương lĩnh của Đảng Cộng hòa.[112] Bác bỏ ý tưởng ấy, Lincoln phát biểu, “Tôi thà chết còn hơn chấp nhận... bất cứ sự nhượng bộ hoặc sự thỏa hiệp nào để có thể sở hữu chính quyền này, là chính quyền chúng ta có được bởi quyền hiến định.”[113] Tuy nhiên, Lincoln ủng hộ Tu chính Corwin được Quốc hội thông qua nhằm bảo vệ quyền sở hữu nô lệ tại những tiểu bang đã có sẵn chế độ nô lệ.[114] Chỉ vài tuần lễ trước khi xảy ra chiến tranh, Lincoln đi xa đến mức viết một bức thư gởi tất cả thống đốc kêu gọi họ ủng hộ việc thông qua Tu chính Corwin, ông xem đó như là nỗ lực tránh nguy cơ ly khai.[115]

Trên đường đến lễ nhậm chức bằng tàu hỏa, Lincoln diễn thuyết trước những đám đông và các viện lập pháp khi ông băng ngang qua lãnh thổ phương Bắc.[116] Ở Baltimore, nhờ Allen Pinkerton, trưởng toán cận vệ, dùng thân mình che Tổng thống tân cử mà ông thoát chết. Ngày 23 tháng 2, 1861, Lincoln phải ngụy trang khi đến Washington, D.C., trong sự bảo vệ của một toán binh sĩ.[117] Nhắm vào dân chúng miền Nam, trong bài diễn văn nhậm chức lần thứ nhất, Lincoln tuyên bố rằng ông không có ý định hủy bỏ chế độ nô lệ ở các tiểu bang miền Nam:

“ Người dân ở các tiểu bang miền Nam nghĩ rằng khi Chính phủ Đảng Cộng hòa lên cầm quyền, tài sản, sự bình yên, và sự an toàn cá nhân của họ sẽ bị đe dọa. Không hề có bất kỳ lý do nào khiến họ nghĩ như thế. Thật vậy, vô số điều chứng minh ngược lại vẫn còn đó và quý vị có thể kiểm tra chúng. Các chứng cứ này có thể được tìm thấy trong hầu hết các diễn từ của người đang nói chuyện với quý vị hôm nay. Xin trích dẫn một trong những bài diễn văn ấy, “Tôi không có mục đích nào, trực tiếp hay gián tiếp, để can thiệp vào chế độ nô lệ ở những tiểu bang vốn đã có sẵn. Tôi tin rằng tôi không có quyền hợp pháp để hành động như thế, mà tôi cũng không có ý định ấy.” ”

Kết thúc bài diễn văn, Tổng thống kêu gọi dân chúng miền Nam: “Chúng ta không phải là kẻ thù, nhưng là bằng hữu. Không thể nào chúng ta trở thành kẻ thù của nhau ... Sợi dây đàn mầu nhiệm của ký ức, trải dài từ những bãi chiến trường và mộ phần của những người yêu nước đến trái tim của mỗi người đang sống, đến chỗ ấm cúng nhất của mỗi mái ấm gia đình, khắp mọi nơi trên vùng đất bao la này, sẽ làm vang tiếng hát của ban hợp xướng Liên bang, khi dây đàn ấy được chạm đến một lần nữa, chắc chắn sẽ như thế, bởi phần tốt lành hơn trong bản chất của chúng ta.”[119]

Chiến tranh

Bài chi tiết: Nội chiến Mỹ

|

Thiếu tá Anderson, Chỉ huy trưởng Đồn Sumter Thiếu tá Anderson, Chỉ huy trưởng Đồn Sumter |

Chỉ huy trưởng Đồn Sumter ở tiểu bang South Carolina, Thiếu tá Robert Anderson, yêu cầu tiếp liệu từ Washington, và khi Lincoln chỉ thị đáp ứng yêu cầu ấy, phe ly khai xem đó là hành động gây chiến. Ngày 12 tháng 4, 1861, lực lượng Liên minh tấn công doanh trại Sumter, buộc họ phải đầu hàng. Chiến tranh bùng nổ. Sử gia Allen Nevins cho rằng tổng thống vừa nhậm chức đã tính toán nhầm khi tin rằng ông có thể duy trì Liên bang.[120] William Tecumseh Sherman, viếng thăm Linconln trong tuần lễ diễn ra lễ nhậm chức, đã “thất vọng trong đau buồn” vì thấy Lincoln không thể nhận ra sự thật là “đất nước đang ngủ mê ngay trên ngọn núi lửa”, và miền Nam đang chuẩn bị cho chiến tranh.[121] Donald đúc kết, “Chính nỗ lực của Lincoln nhiều lần cố tránh va chạm trong thời gian giữa lễ nhậm chức và trận Đồn Sumter chỉ ra rằng ông trung thành với lời hứa sẽ không phải là người khởi phát cuộc huynh đệ tương tàn. Mặt khác, ông cũng thề hứa không chịu để các đồn binh bị thất thủ. Giải pháp duy nhất cho phe Liên minh là họ phải khai hỏa trước; và họ đã hành động."[122]

Ngày 15 tháng 4, Lincoln kêu gọi các tiểu bang gởi 75 000 binh sĩ tái chiếm các đồn binh, bảo vệ Washington, và “duy trì Liên bang”, theo ông, vẫn đang còn nguyên vẹn bất kể hành động của những bang ly khai. Lời kêu gọi này buộc các tiểu bang phải quyết định dứt khoát. Virginia tuyên bố ly khai, liền được ban thưởng để trở thành thủ đô của Liên minh. Trong vòng hai tháng, North Carolina, Tennessee, và Arkansas cũng biểu quyết ly khai. Cảm tình ly khai phát triển ởMissouri và Maryland, nhưng chưa đủ mạnh để chiếm ưu thế, trong khi Kentucky cố tỏ ra trung lập.[123]

Binh sĩ di chuyển về hướng nam đến Washington để bảo vệ thủ đô, đáp lời kêu gọi của Lincoln. Ngày 19 tháng 4, những đám đông chủ trương ly khai ở Baltimore chiếm đường sắt dẫn về thủ đô. George William Brown, Thị trưởng Baltimore, và một số chính trị gia khả nghi khác ở Maryland bị cầm tù mà không cần trát lệnh, Lincoln đình chỉ quyền công dân được xét xử trước tòa.[124] John Merryman, thủ lĩnh nhóm ly khai ở Maryland, thỉnh cầu Chánh án Tối cao Pháp viện Roger B. Taney ra phán quyết cho rằng vụ bắt giữ vụ bắt giữ Merryman mà không xét xử là vi phạm pháp luật. Taney ra phán quyết, theo đó Merryman phải được trả tự do, nhưng Lincoln phớt lờ phán quyết. Từ đó, và trong suốt cuộc chiến, Lincoln bị chỉ trích dữ dội, thường khi bị lăng mạ, bởi những đảng viên Dân chủ chống chiến tranh.[125]

Hành xử quyền lực trong thời chiến

|

|

3 tháng 10, 1862

|

Sau khi Đồn Sumter bị thất thủ, Lincoln nhận ra tầm quan trọng của việc trực tiếp nắm quyền chỉ huy nhằm kiểm soát cuộc chiến và thiết lập chiến lược toàn diện để trấn áp phe nổi loạn. Đối đầu với cuộc khủng hoảng chính trị và quân sự chưa từng có, Lincoln, với tư cách là Tổng Tư lệnh Quân lực, sử dụng quyền lực chưa từng có. Ông mở rộng những quyền đặc biệt trong chiến tranh, áp đặt lệnh phong tỏa trên tất cả thương cảng của Liên minh, ra lệnh cầm tù không qua xét xử hàng ngàn người bị nghi là ủng hộ Liên minh. Quốc hội và công luận miền bắc ủng hộ ông. Hơn nữa, Lincoln phải đấu tranh để củng cố sự ủng hộ mạnh mẽ từ những tiểu bang có nô lệ ở vùng biên, và phải kiềm chế cuộc chiến không trở thành một cuộc tranh chấp quốc tế.[126]

Nỗ lực dành cho cuộc chiến chiếm hết thời gian và tâm trí của Lincoln cũng như khiến ông trở nên tâm điểm của sự dèm pha và miệt thị. Nhóm phản chiến trong Đảng Dân chủ chỉ trích Lincoln không chịu thỏa hiệp trong vấn đề nô lệ, trong khi nhóm cấp tiến trong Đảng Cộng hòa phê phán ông hành động quá chậm trong nỗ lực bãi nô.[127] Ngày 6 tháng 8, 1861, Lincoln ký ban hành Luật Tịch biên, cho phép tịch biên tài sản và giải phóng nô lệ của những người ủng hộ Liên minh trong cuộc chiến. Trong thực tế, dù ít khi được áp dụng, luật này đánh dấu sự ủng hộ chính trị dành cho nỗ lực bãi bỏ chế độ nô lệ.[128]

Lincoln mượn từ Thư viện Quốc hội quyển Elements of Military Art and Science của Henry Halleck để đọc và nghiên cứu về quân sự.[129] Lincoln nhẫn nại xem xét từng báo cáo gởi bằng điện tín từ Bộ Chiến tranh ở Washington D. C. , tham vấn các thống đốc tiểu bang, một số tướng lãnh được tuyển chọn dựa trên thành tích của họ. Tháng 1 năm 1862, sau nhiều lời than phiền về sự thiếu hiệu quả cũng như những hành vi vụ lợi ở Bộ Chiến tranh, Licoln bổ nhiệm Edwin Stanton thay thế Cameron trong cương vị bộ trưởng. Stanton là một trong số nhiều đảng viên Dân chủ bỏ sang đảng Cộng hòa dưới quyền lãnh đạo của Lincoln.[130] Mỗi tuần hai lần, Lincoln họp với nội các. Ông học hỏi từ Tướng Henry Halleck về sự cần thiết kiểm soát các điểm chiến lược, như sông Mississippi;[131] ông cũng biết rõ tầm quan trọng của thị trấn Vicksburg, và hiểu rằng cần phải triệt tiêu sức mạnh quân sự của đối phương chứ không chỉ đơn giản là chiếm được lãnh thổ.[132]

[sửa]Tướng McClellan

Năm 1861, Lincoln bổ nhiệm Thiếu tướng George B. McClellan làm tổng tham mưu trưởng quân lực Liên bang thay thế tướng Winfield Scott về hưu.[133] Tốt nghiệp Trường Võ bị West Point, từng lãnh đạo công ty đường sắt, và đảng viên Dân chủ từ Pensylvania, McClellan phải mất đến vài tháng để lập kế hoạch cho chiến dịch Penisula nhằm chiếm Richmond để tiến về thủ đô của Liên minh. Sự chậm trễ này đã gây bối rối cho Lincoln và Quốc hội.[134]

|

Lincoln và McClellan sau trận Antietam Lincoln và McClellan sau trận Antietam |

Tháng 3 năm 1862, Lincoln bãi chức McClellan và bổ nhiệm Henry Wager Halleck thay thế. Trên biển, chiến hạm CSS Virginia gây thiệt hại ba chiến hạm của Liên bang ở Norfolk, Virginia trước khi bị chiến hạm USS Monitor đánh bại.[135] Trong lúc tuyệt vọng, Lincoln phải mời McClellan trở lại lãnh đạo lực lượng vũ trang khu vực Washington. Hai ngày sau, lực lượng của Tướng Lee băng qua sông Potomac tiến vào Maryland tham gia trận Antietam trong tháng 9 năm 1862.[136] Đây là một trong những trận đánh đẫm máu nhất trong lịch sử nước Mỹ dù chiến thắng thuộc về Liên bang, và cũng là cơ hội để Lincoln công bố bản Tuyên ngôn Giải phóng Nô lệ nhằm tránh những đồn đoán cho rằng Lincoln phải công bố bản tuyên ngôn vì đang ở trong tình thế tuyệt vọng.[137] McClellan chống lại lệnh của tổng thống yêu cầu truy đuổi Tướng Lee, trong khi đồng đội của ông, Tướng Don Carlos Buell không chịu động binh đánh quân nổi dậy ở phía đông Tennessee. Lincoln bổ nhiệm William Rosecrant thay thế Buell; sau cuộc bầu cử giữa nhiệm kỳ, ông chọn Ambrose Burnside thay thế McClellan. Hai nhà lãnh đạo quân sự mới đều có quan điểm chính trị ôn hòa và đều ủng hộ vị tổng tư lệnh quân lực.[138]

Tháng 12, do vội vàng mở cuộc tấn công băng qua sông Rappahannock, Burnside bị Lee đánh bại trong trận Fredericksburg khiến hàng ngàn binh sĩ bất mãn và đào ngũ trong năm 1863.[139]

Trong cuộc bầu cử giữa kỳ năm 1862, đảng Cộng hòa mất nhiều ghế ở Viện Dân biểu do cử tri bất bình với chính phủ vì không thể kết thúc sớm cuộc chiến, và vì nạn lạm phát, tăng thuế, những đồn đại về tham ô, và nỗi e sợ thị trường lao động sẽ sụp đổ nếu giải phóng nô lệ. Tuyên ngôn Giải phóng Nô lệ được công bố vào tháng 9 đã giúp đảng Cộng hòa giành phiếu bầu ở các khu vực nông thông vùng New Englandvà phía bắc vùng Trung Tây, nhưng mất phiếu ở các đô thị và phía nam vùng Tây Bắc. Đảng Dân chủ được tiếp thêm sức mạnh và hoạt động tốt ở Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, và New York. Tuy nhiên, đảng Cộng hòa vẫn duy trì thế đa số ở Quốc hội và các tiểu bang quan trọng ngoại trừ New York. Theo tờ Cincinnati, cử tri “thất vọng vì thấy cuộc chiến tiếp tục kéo dài, cũng như sự cạn kiệt tài nguyên quốc gia mà không có sự tiến bộ nào.” [140]

[sửa]Tuyên ngôn Giải phóng Nô lệ

|

Lincoln trình bày trước nội các bản thảo đầu tiên của bản Lincoln trình bày trước nội các bản thảo đầu tiên của bản Tuyên ngôn Giải phóng Nô lệ. |

Lincoln hiểu rằng quyền lực của chính quyền liên bang để giải phóng nô lệ đang bị hạn chế bởi Hiến pháp, mà hiến pháp, từ trước năm 1865, đã dành quyền này cho các tiểu bang. Lúc bắt đầu cuộc chiến, Lincoln cố thuyết phục các tiểu bang chấp nhận giải phóng nô lệ có bồi thường (nhưng chỉ được Washington, D. C. áp dụng) Ông bác bỏ các đề nghị giới hạn việc giải phóng nô lệ theo khu vực địa lý.[141]

Ngày 19 tháng 6, 1862, với sự ủng hộ của Lincoln, Quốc hội thông qua luật cấm chế độ nô lệ trên toàn lãnh thổ liên bang. Tháng 7, dự luật thứ hai được thông qua, thiết lập trình tự tài phán để tiến hành giải phóng nô lệ của những chủ nô bị kết án ủng hộ phe phiến loạn. Dù không tin Quốc hội có quyền giải phóng nô lệ trong lãnh thổ các tiểu bang, Lincoln phê chuẩn dự luật để bày tỏ sự ủng hộ dành cho ngành lập pháp.

Ông cảm nhận rằng tổng thống trong cương vị tổng tư lệnh quân lực có thể sử dụng quyền hiến định hành động trong tình trạng chiến tranh để thực thi luật pháp, và ông lập kế hoạch hành động. Ngay trong tháng 6, Lincoln thảo luận với nội các nội dung bản Tuyên ngôn, trong đó ông viết, “như là một biện pháp quân sự cần thiết và thích đáng, từ ngày 1 tháng 1, 1863, mọi cá nhân bị xem là nô lệ trong các tiểu bang thuộc Liên minh, từ nay và vĩnh viễn, được tự do.”[142]

Trong chỗ riêng tư, Lincoln khẳng quyết rằng không thể chiến thắng mà không giải phóng nô lệ. Tuy nhiên, phe Liên minh và thành phần chống chiến tranh tuyên truyền rằng giải phóng nô lệ là rào cản đối với nỗ lực thống nhất đất nước. Lincoln giải thích rằng mục tiêu chính của ông trong cương vị tổng thống là bảo vệ sự thống nhất của Liên bang:[143]

“ Mục tiêu to lớn của tôi trong cuộc chiến này là cứu Liên bang, chứ không phải là cứu hay hủy diệt chế độ nô lệ. Nếu có thể cứu Liên bang mà không cần phải giải phóng nô lệ thì tôi sẽ làm như thế, còn nếu có thể cứu Liên bang mà phải giải phóng tất cả nô lệ tôi sẽ làm như thế; và nếu có thể cứu Liên bang mà chỉ cần giải phóng một số nô lệ và để mặc những nô lệ còn lại, tôi cũng sẽ làm. Những gì tôi làm liên quan đến chế độ nô lệ và chủng tộc da màu là do tôi tin rằng nó giúp chúng ta cứu Liên bang...[144] ”

Công bố ngày 22 tháng 9, 1862, bản Tuyên ngôn Giải phóng Nô lệ có hiệu lực từ ngày 1 tháng 1, 1863, tuyên bố giải phóng nô lệ trong 10 tiểu bang ngoài vòng kiểm soát của Liên bang, với sự miễn trừ dành cho những khu vực trong hai tiểu bang thuộc Liên bang.[145] Quân đội Liên bang càng tiến sâu về phía Nam càng có nhiều nô lệ được tự do cho đến hơn ba triệu nô lệ trong lãnh thổ Liên minh được giải phóng. Lincoln nhận xét về bản Tuyên ngôn, “Chưa bao giờ trong đời tôi tin quyết về những gì tôi đang làm là đúng như khi tôi ký văn kiện này.” [146]

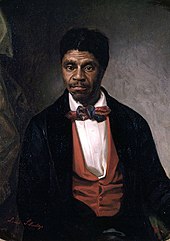

Sau khi ban hành Tuyên ngôn Giải phóng Nô lệ, tuyển mộ cựu nô lệ vào quân đội là chủ trương chính thức của chính phủ. Lúc đầu còn miễn cưỡng, nhưng từ mùa xuân năm 1863, Lincoln khởi xướng chương trình “tuyển mộ đại trà binh sĩ da đen”. Trong thư gởi Andrew Johnson, thống đốc quân sự Tennessee, Lincoln viết, “Chỉ cần quang cảnh 50 000 chiến binh da đen được huấn luyện và trang bị đầy đủ cũng có thể chấm dứt cuộc nổi loạn ngay lập tức.” [147] Cuối năm 1863, theo hướng dẫn của Lincoln, Tướng Lorenzo Thomas tuyển mộ 20 trung đoàn da đen từ Thung lũng Mississippi.[148] Frederick Douglass có lần nhận xét, “Khi gặp Lincoln, chưa bao giờ tôi nhớ đến xuất thân thấp kém, hoặc màu da không được ưa thích của mình.” [149]

[sửa]Diễn văn Gettysburg

Bài chi tiết: Diễn văn Gettysburg

Tháng 7 năm 1863, quân Liên bang thắng lớn trong trận Gettysburg. Trên chính trường, nhóm Copperheads bị thất bại trong kỳ tuyển cử mùa thu ở Ohio, nhờ đó Lincoln duy trì sự ủng hộ bên trong đảng cùng vị thế chính trị vững chãi đủ để tái thẩm định cuộc chiến. Tình thế thuận lợi cho Lincoln vào thời điểm ông đọc bài diễn văn tại nghĩa trang Gettysburg.[150] Trái với lời tiên đoán của Lincoln, “Thế giới không quan tâm, cũng chẳng nhớ những gì chúng ta nói ở đây,” bài diễn văn đã trở nên một trong những diễn từ được trích dẫn nhiều nhất trong lịch sử Mỹ Quốc.[6]

Diễn văn Gettysburg được đọc trong lễ cung hiến Nghĩa trang Liệt sĩ Quốc gia tại Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, vào chiều thứ Năm, ngày 19 tháng 11, 1863. Chỉ với 273 từ, trong bài diễn văn kéo dài ba phút này, Lincoln nhấn mạnh đất nước được sản sinh, không phải năm 1789, mà từ năm 1776, “được thai nghén trong Tự do, được cung hiến cho niềm xác tín rằng mọi người sinh ra đều bình đẳng.” Ông định nghĩa rằng chiến tranh là sự hi sinh đấu tranh cho nguyên tắc tự do và bình đẳng cho mọi người. Giải phóng nô lệ là một phần của nỗ lực ấy. Ông tuyên bố rằng cái chết của các chiến sĩ dũng cảm là không vô ích, rằng chế độ nô lệ sẽ thất bại và cáo chung, tương lai của nền dân chủ sẽ được bảo đảm, và “chính quyền của dân, do dân, vì dân sẽ không lụi tàn khỏi mặt đất.” Lincoln đúc kết rằng cuộc nội chiến có một mục tiêu cao quý – sản sinh một nền tự do mới cho dân tộc.[151][152]

[sửa]Tướng Grant

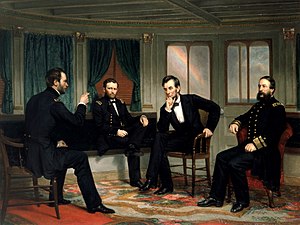

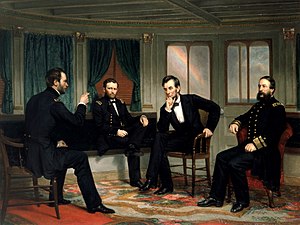

|

Tổng thống Lincoln (giữa) ngồi với các tướng lĩnh (từ trái) Sherman, Tổng thống Lincoln (giữa) ngồi với các tướng lĩnh (từ trái) Sherman,Grant và Đô đốc Porter, tháng 3, 1865 |

Sự kiện Meade không thể khống chế đạo quân của Lee khi ông này triệt thoái khỏi Gettysburg cùng với sự thụ động kéo dài của Binh đoàn Potomac khiến Lincoln tin rằng cần có sự thay đổi ở vị trí tư lệnh mặt trận. Chiến thắng của Tướng Ulysses S. Grant trong trận Shiloh và trong chiến dịch Vicksburg tạo ấn tượng tốt đối với Lincoln.[153] Vào năm 1864, Grant phát động Chiến dịch Overland đẫm máu thường được gọi là chiến tranh tiêu hao, khiến phía Liên bang thiệt hại nặng nề trong các mặt trận như Wilderness và Cold Harbor. Dù được hưởng lợi thế của phía phòng thủ, quân đội Liên minh cũng bị tổn thất không kém.[154]

Do không có nguồn lực dồi dào, đạo quân của Lee cứ hao mòn dần qua mỗi trận chiến, bị buộc phải đào hào phòng thủ bên ngoàiPetersburg, Virginia trong vòng vây của quân đội Grant.

Linconln cho phép Grant phá hủy cơ sở hạ tầng của Liên minh như nông trang, đường sắt, và cầu cống nhằm làm suy sụp tinh thần cũng như làm suy yếu khả năng kinh tế của đối phương. Di chuyển đến Petersburg, Grant chặn ba tuyến đường sắt từ Richmond, Virginia về phía nam tạo điều kiện cho Tướng Sherman và Tướng Philip Sheridan hủy phá các nông trang và các thị trấn ở Thung lũng Shenandoah thuộc Virginia. Vào ngày 1 tháng 4 năm 1865, Grant thọc sâu vào sườn của lực lượng của Lee trong trận Five Forks và bao vây Petersburg, chính phủ Liên minh phải di tản khỏi Richmond. Lincoln đến thăm thủ đô của Liên minh khi vừa bị thất thủ, người da đen được tự do chào đón ông như một vị anh hùng trong khi người da trắng tỏ vẻ lạnh lùng với tổng thống của phe chiến thắng. Vào ngày 9 tháng 4 năm 1865, tại làng Appomattox Court House, Lee đầu hàng trước Grant, kết thúc cuộc nội chiến.[155]

[sửa]Năm 1864, tái tranh cử

Là chính trị gia lão luyện, Lincoln không chỉ có khả năng đoàn kết tất cả phe phái chính trong đảng Cộng hòa mà còn thu phục những người Dân chủ như Edwin M. Stanton và Andrew Johnson. Ông dành nhiều giờ trong tuần để đàm đạo với các chính trị gia đến từ khắp đất nước, và sử dụng ảnh hưởng rộng lớn của ông để tạo sự đồng thuận giữa các phe nhóm trong đảng, xây dựng hậu thuẫn cho các chính sách của ông, và đối phó với nỗ lực của nhóm cấp tiến đang cố loại ông khỏi liên danh năm 1864.[156][157]

Chiến thắng áp đảo của Lincoln (đỏ) trong kỳ bầu cử 1864. Các tiểu bang (nâu) và lãnh thổ (nâu nhạt) miền nam không tham dự

|

| Lincoln đọc diễn văn nhậm chức lần thứ hai năm 1865 |

Đại hội đảng năm 1864 chọn Andrew Johnson đứng cùng liên danh với Lincoln. Nhằm mở rộng liên minh chính trị hầu lôi cuốn các đảng viên Dân chủ và Cộng hòa, Lincoln tranh cử dưới danh nghĩa của Đảng Liên hiệp Quốc gia tân lập.[158]

Khi các chiến dịch mùa xuân của Grant đi vào bế tắc trong khi tổn thất tiếp tục gia tăng, sự thiếu vắng các chiến thắng quân sự phủ bóng trên triển vọng đắc cử của Tổng thống, nhiều đảng viên Cộng hòa trên khắp nước e sợ Lincoln sẽ thất cử.[159]

Khi cánh chủ hòa trong đảng Dân chủ gọi cuộc chiến là một “thất bại” thì ứng cử viên của đảng, Tướng George B. McClellan, ủng hộ chiến tranh và lên tiếng bác bỏ luận cứ của phe chủ hòa. Lincoln cấp thêm lính cho Grant, đồng thời vận động đảng của ông tăng cường hỗ trợ cho Grant. Trong tháng 9, Thắng lợi của Liên bang khi Sherman chiếm Atlanta và David Farragut chiếm Mobile dập tắt mọi hoài nghi;[160]

Đảng Dân chủ bị phân hóa trầm trọng, một số nhà lãnh đạo và phần lớn quân nhân quay sang ủng hộ Lincoln. Một mặt, Đảng Liên hiệp Quốc gia đoàn kết chặt chẽ hỗ trợ cho Lincoln khi ông tập chú vào chủ đề giải phóng nô lệ; mặt khác, các chi bộ Cộng hòa cấp tiểu bang nỗ lực hạ giảm uy tín phe chủ hòa.[161] Lincoln thắng lớn trong cuộc tuyển cử, giành được phiếu bầu của tất cả ngoại trừ ba tiểu bang.[162]

Ngày 4 tháng 3, 1865, trong bài diễn văn nhậm chức lần thứ hai, Lincoln bày tỏ rằng sự tổn thất lớn lao từ hai phía là do ý chỉ của Thiên Chúa. Sử gia Mark Noll xếp diễn từ này vào trong “một số ít các văn bản hàm chứa tính thiêng liêng, nhờ đó người dân Mỹ ý thức được vị trí của mình trên thế giới.”

“ Mơ ước khi hi vọng – khẩn thiết lúc nguyện cầu – chúng ta mong cuộc chiến đau thương này sớm chấm dứt. Song, theo ý chỉ của Thiên Chúa, nó vẫn tiếp diễn, cho đến khi tất cả của cải từng được dồn chứa bởi sự lao dịch khốn cùng của người nô lệ trong suốt 250 năm sẽ bị tiêu tan, cho đến khi mỗi một giọt máu ứa ra từ những lằn đòn sẽ bị đáp trả bằng những nhát chém, như đã được cảnh báo từ 3 000 năm trước, và cần được nhắc lại hôm nay, “sự đoán xét của Chúa là chân lý và hoàn toàn công chính”.[163]

Không ác tâm với bất cứ ai nhưng nhân ái với mọi người, và kiên định trong lẽ phải. Khi Chúa cho chúng ta nhận ra lẽ phải, hãy tranh đấu để hoàn thành sứ mạng được giao: hàn gắn vết thương của dân tộc, chăm sóc các chiến sĩ, những người vợ góa, những trẻ mồ côi – hết sức mình tạo lập một nền hòa bình vững bền và công chính, cho chúng ta, và cho mọi dân tộc.[164] ”

[sửa]Tái thiết

Tôi luôn luôn thấy rằng một tấm lòng thương xót kết quả nhiều hơn một nền công lý nghiêm nhặt.

Abraham Lincoln[165]

Thời kỳ tái thiết đã khởi đầu ngay từ lúc còn chiến tranh, khi Lincoln và các phụ tá của ông tính trước phương cách giúp các tiểu bang miền nam tái hội nhập, giải phóng nô lệ, và quyết định số phận của giới lãnh đạo Liên minh. Không lâu sau khi Tướng Lee đầu hàng, khi được hỏi nên đối xử với phe thất trận như thế nào, Lincoln trả lời, “Hãy để họ thoải mái".[166] Trong nỗ lực tiến hành chính sách hòa giải, Lincoln nhận được sự ủng hộ của nhóm ôn hòa, nhưng bị chống đối bởi nhóm cấp tiến trong đảng Cộng hòa nhự Dân biểu Thaddeus Stevens, các Thượng Nghị sĩ Charles Summer và Benjamin Wade, là những đồng minh chính trị của ông trong các vấn đề khác. Quyết tâm tìm ra giải pháp hiệp nhất dân tộc mà không thù địch với miền Nam, Lincoln thúc giục tổ chức bầu cử sớm theo các điều khoản phóng khoáng. Tuyên cáo Ân xá của tổng thống ngày 8 tháng 12, 1863 công bố không buộc tội những ai không có chức vụ trong Liên minh, chưa từng ngược đãi tù binh Liên bang, và chịu ký tuyên thệ trung thành với Liên bang.[167]

Sự chọn lựa nhân sự của Lincoln là nhằm giữ hai nhóm ôn hòa và cấp tiến cùng làm việc với nhau. Ông bổ nhiệm Salmon P. Chase thuộc nhóm cấp tiến vào Tối cao Pháp viện thay thế Chánh án Taney.

Sau khi Tuyên ngôn Giải phóng Nô lệ có hiệu lực, dù không được áp dụng trên tất cả tiểu bang, Lincoln gia tăng áp lực yêu cầu Quốc hội ra một bản tu chính đặt chế độ nô lệ ngoài vòng pháp luật trên toàn lãnh thổ. Lincoln tuyên bố rằng một bản tu chính như thế sẽ “giải quyết dứt điểm toàn bộ vấn đề”.[168] Tháng 6 năm 1864, một dự luật tu chính được trình Quốc hội nhưng không được thông qua vì không đủ đa số hai phần ba. Việc thông qua dự luật trở thành một trong những chủ đề vận động trong cuộc bầu cử năm 1864. Ngày 13 tháng 1, 1865, sau một cuộc tranh luận dài ở Viện Dân biểu, dự luật được thông qua và được gửi đến các viện lập pháp tiểu bang để phê chuẩn[169] để trở thành Tu chính án thứ mười ba của Hiến pháp Hoa Kỳ vào ngày 6 tháng 12, 1865.[170]

Khi cuộc chiến sắp kết thúc, kế hoạch tái thiết của tổng thống tiếp tục được điều chỉnh. Tin rằng chính phủ liên bang có một phần trách nhiệm đối với hàng triệu nô lệ được giải phóng, Lincoln ký ban hàng đạo luật Freedman’s Bureau thiết lập một cơ quan liên bang đáp ứng các nhu cầu của những cựu nô lệ, cung ứng đất thuê trong hạn ba năm với quyền được mua đứt cho những người vừa được tự do.

]Tái định nghĩa khái niệm cộng hòa và chủ nghĩa cộng hòa

|

Tấm ảnh cuối cùng của Lincoln, tháng 3, 1865. Tấm ảnh cuối cùng của Lincoln, tháng 3, 1865. |

Những sử gia đương đại như Harry Jaffa, Herman Belz, John Diggins, Vernon Burton, và Eric Foner đều nhấn mạnh đến nỗ lực tái định nghĩa các giá trị cộng hòa của Lincoln. Từ đầu thập niên 1850 khi các luận cứ chính trị đều hướng về tính thiêng liêng của Hiến pháp, Lincoln đã tập chú vào bản Tuyên ngôn Độc lập, xem văn kiện này là nền tảng của các giá trị chính trị của nước Mỹ mà ông gọi là “thành lũy” của chủ nghĩa cộng hòa.[171]

Sự kiện bản Tuyên ngôn nhấn mạnh đến quyền tự do và sự bình đẳng dành cho mọi người, trái ngược với Hiến pháp dung chịu chế độ nô lệ, đã làm thay đổi chiều hướng tranh luận. Luận điểm của Lincoln đã gây dựng được ảnh hưởng vì ông làm sáng tỏ nền tảng đạo đức của chủ nghĩa cộng hòa, thay vì chỉ biết tuân thủ hiến pháp.[172]

[sửa]Các đạo luật

Nội các Lincoln[173]

Chức vụ Tên Nhiệm kỳ

Tổng thống Abraham Lincoln 1861–1865

Phó Tổng thống Hannibal Hamlin 1861–1865

Andrew Johnson 1865

Bộ trưởng Ngoại giao William H. Seward 1861–1865

Bộ trưởng Chiến tranh Simon Cameron 1861–1862

Edwin M. Stanton 1862–1865

Bộ trưởng Ngân khố Salmon P. Chase 1861–1864

William P. Fessenden 1864–1865

Hugh McCulloch 1865

Bộ trưởng Tư pháp Edward Bates 1861–1864

James Speed 1864–1865

Bộ trưởng Bưu điện Montgomery Blair 1861–1864

William Dennison, Jr. 1864–1865

Bộ trưởng Hải quân Gideon Welles 1861–1865

Bộ trưởng Nội vụ Caleb B. Smith 1861–1862

John P. Usher 1863–1865

Lincoln trung thành với chủ thuyết của đảng Whig về chức vụ tổng thống, theo đó Quốc hội có trách nhiệm làm luật và nhánh hành pháp thực thi luật pháp. Chỉ có bốn dự luật đã được Quốc hội thông qua đã bị Lincoln phủ quyết.[174] Năm 1862, ông ký ban hành đạo luật Homestead bán cho người dân với giá rất thấp hàng triệu héc-ta đất chính phủ đang sở hữu. Đạo luật Morrill Land-Grant Colleges ký năm 1862 cung ứng học bổng chính phủ cho các trường đại học nông nghiệp tại mỗi tiểu bang. Đạo luật Pacific Raiway năm 1862 và 1864 dành sự hỗ trợ của liên bang cho công trình xây dựng đường sắt xuyên lục địa hoàn thành năm 1869.[175]

Lincoln cũng mở rộng ảnh hưởng kinh tế của chính phủ liên bang sang các lãnh vực khác. Đạo luật National Banking cho phép thành lập hệ thống ngân hàng quốc gia cung ứng mạng lưới tài chính dồi dào trên toàn quốc, cũng như thiết lập nền tiền tệ quốc gia. Năm 1862, Quốc hội đề xuất và tổng thống phê chuẩn việc thành lập Bộ Nông nghiệp.[176] Năm 1862, Lincoln cử Tướng John Pope bình định cuộc nổi dậy của bộ tộc Sioux. Tổng thống cũng cho lập kế hoạch cải cách chính sách liên bang đối với người da đỏ.[177]

Lincoln là nhân tố chính trong việc công nhận Lễ Tạ ơn là quốc lễ của Hoa Kỳ.[178] Trước nhiệm kỳ tổng thống của Lincoln, Lễ Tạ ơn là ngày lễ phổ biến ở vùng New England từ thế kỷ 17. Năm 1863, Lincoln tuyên bố thứ Năm cuối cùng của tháng Mười là ngày cử hành Lễ Tạ ơn.[178]

Tối cao Pháp viện

Lincoln bổ nhiệm năm thẩm phán cho tòa án tối cao. Noah Haynes Swayne, được đề cử ngày 21 tháng 1, 1862 và bổ nhiệm ngày 24 tháng 1, 1862; ông là luật sư, chống chế độ nô lệ và ủng hộ Liên bang. Samuel Freeman Miller, được đề cử và bổ nhiệm ngày 16 tháng 7, 1862; ông ủng hộ Lincoln trong cuộc bầu cử năm 1860, và là người chủ trương bãi nô. David Davis, được đề cử ngày 1 tháng 12, 1862 và bổ nhiệm ngày 8 tháng 12, 1862; ông là người điều hành chiến dịch tranh cử năm 1860 của Lincoln, từng là thẩm phán tòa phúc thẩm liên bang ở Illinois. Stephen Johnson Field, được đề cử ngày 6 tháng 3, 1863 và bổ nhiệm ngày 10 tháng 3, 1863; từng là thẩm phán tòa tối cao bang California. Cuối cùng là Bộ trưởng Ngân khố của Lincoln, Salmon P. Chase, được đề cử và bổ nhiệm trong ngày 6 tháng 12, 1862 vào chức vụ Chánh án Tối cao Pháp viện Hoa Kỳ. Lincoln tin Chase là một thẩm phán có khả năng, sẽ hỗ trợ công cuộc tái thiết trong lĩnh vực tư pháp, và sự bổ nhiệm này sẽ liên kết các nhóm trong đảng Cộng hòa.[179]

Các Tiểu bang gia nhập Liên bang

Ngày 20 tháng 6, 1863, bang West Virginia xin gia nhập Liên bang, bao gồm những hạt cực tây bắc từng tách khỏi tiểu bang sau khi bang này rút lui khỏi Liên bang. Nevada, tiểu bang thứ ba thuộc vùng viễn tây được gia nhập ngày 31 tháng 10, 1864.[180]

Ám sát

Bài chi tiết: vụ ám sát Abraham Lincoln

|

Trong lô dành riêng cho tổng thống ở Nhà hát Ford, (từ trái) Trong lô dành riêng cho tổng thống ở Nhà hát Ford, (từ trái)Henry Rathbone, Clara Harris, Mary Todd Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln, và John Wilkes Booth. |

Một diễn viên nổi tiếng, John Wilkes Booth, là gián điệp của Liên minh đến từ Maryland; dù chưa bao giờ gia nhập quân đội Liên minh, Booth có mối quan hệ với mật vụ Liên minh.[181] Năm 1864, Booth lên kế hoạch bắt cóc Lincoln để đòi thả tù binh Liên minh. Nhưng sau khi dự buổi diễn thuyết của Lincoln vào ngày 11 tháng 4, 1865, Booth giận dữ thay đổi kế hoạch và quyết định ám sát tổng thống.[182] Dò biết Tổng thống, Đệ nhất Phu nhân, và Tướng Ulysses S. Grant sẽ đến Nhà hát Ford, Booth cùng đồng bọn lập kế hoạch ám sát Phó Tổng thống Andrew Johnson, Bộ trưởng Ngoại giao William H. Seward, và Tướng Grant. Ngày 14 tháng 4, Lincoln đến xem vở kịch “Our American Cousin” mà không có cận vệ chính Ward Hill Lamon đi cùng. Đến phút chót, thay vì đi xem kịch, Grant cùng vợ đến Philadelphia.[183]

Trong lúc nghỉ giải lao, John Parker, cận vệ của Lincoln, rời nhà hát cùng người đánh xe đến quán rượu Star kế cận. Lợi dụng cơ hội Tổng thống ngồi trong lô danh dự mà không có cận vệ bên cạnh, khoảng 10 giờ tối, Booth lẻn vô và bắn vào sau đầu của Tổng thống từ cự ly gần. Thiếu tá Henry Rathbone chụp bắt Booth nhưng hung thủ đâm trúng Rathbone và trốn thoát.[184][185]

Sau mười ngày đào tẩu, người ta tìm thấy Booth tại một nông trang ở Virginia, khoảng 30 dặm (48 km) phía nam Washington D. C. Ngày 26 tháng 4, sau một cuộc đụng độ ngắn, Booth bị binh sĩ Liên bang giết chết.[186]

Sau cơn hôn mê kéo dài chín giờ, Lincoln từ trần lúc 7g 22 sáng ngày 15 tháng 4. Mục sư Phineas Densmore Gurley thuộc Giáo hội Trưởng Lão được mời cầu nguyện sau khi Bộ trưởng Chiến tranh Stanton chào tiễn biệt và nói, “Nay ông thuộc về lịch sử.”[187]

Thi thể của Lincoln được phủ quốc kỳ và được các sĩ quan Liên bang hộ tống dưới cơn mưa về Tòa Bạch Ốc trong tiếng chuông nhà thờ của thành phố. Phó Tổng thống Johnson tuyên thệ nhậm chức lúc 10:00 sáng ngay trong ngày Tổng thống bị ám sát. Suốt ba tuần lễ, đoàn tàu hỏa dành cho tang lễ Tổng thống mang thi thể ông đến các thành phố trên khắp miền Bắc đến các lễ tưởng niệm có hàng trăm ngàn người tham dự, trong khi nhiều người khác tụ tập dọc theo lộ trình giăng biểu ngữ, đốt lửa, và hát thánh ca.[188][189]

[sửa]Niềm tin tôn giáoXem thêm thông tin: Abraham Lincoln và tôn giáo

|

Lincoln, tranh George Healy, năm 1869 Lincoln, tranh George Healy, năm 1869 |

Giới học giả viết nhiều về các chủ đề liên quan đến đức tin và triết lý sống của Lincoln. Ông thường sử dụng hình ảnh và ngôn ngữ tôn giáo để trình bàyđức tin cá nhân hoặc để thuyết phục cử tọa, phần lớn trong số họ là tín hữu Kháng Cách theo trào lưu Tin Lành.[190] Dù chưa bao giờ chính thức gia nhập giáo hội nào, Lincoln rất gần gũi với Kinh Thánh, thường xuyên trích dẫn và tán dương Kinh Thánh.[191]

Trong thập niên 1840, Lincoln ngả theo ‘’Học thuyết Tất yếu’’ tin rằng tâm trí con người ở dưới sự kiểm soát của một quyền lực cao hơn.[192] Đến thập niên 1850, Lincoln thừa nhận “ơn thần hựu” theo cách chung, nhưng hiếm khi sử dụng ngôn ngữ và hình ảnh tôn giáo của người Tin Lành. Ông dành sự tôn trọng cho chủ nghĩa cộng hòa của những nhà lập quốc gần như là niềm tin tôn giáo.[193] Song, khi đau khổ vì cái chết của con trai ông, Edward, Lincoln thường xuyên nhìn nhận rằng ông cần phải trông cậy Thiên Chúa.[194] Khi một con trai khác của Lincoln, Willie, lìa đời trong tháng 2, 1862, ông càng hướng về tôn giáo để tìm câu giải đáp và sự an ủi.[195]

[sửa]Vị trí trong lịch sử

Theo bảng Xếp hạng Tổng thống trong Lịch sử Hoa Kỳ được thực hiện từ thập niên 1940, Lincoln luôn có tên trong ba người đứng đầu, thường khi là nhân vật số 1.[196] Bản thân ông luôn coi các vị Quốc phụ của Hoa Kỳ - George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton và James Madison - là những tấm gương ngời sáng để noi theo. Ông cho rằng các bậc tiền bối ấy là những con người sắt đá.[1]

Ông được khen ngợi như một chính trị gia vĩ đại, ngang tầm với Tổng thống Washington và Thủ tướng Winston Churchill của nước Anh trong thế kỷ 20.[2]Trong phần lớn các cuộc khảo sát bắt đầu thực hiện từ năm 1948, Lincoln được xếp vào hàng đầu: Schlesinger 1948, Schlesinger 1962, 1982 Murray Blessing Survey, Chicago Tribune 1982 poll, Schlesinger 1996, CSPAN 1996, Ridings-McIver 1996, Time 2008, and CSPAN 2009. Đại thể, những tổng thống chiếm ba vị trí đầu là 1) Lincoln; 2) George Washington; và 3) Franklin D. Roosevelt, mặc dù đôi khi cũng có sự đảo ngược vị trí với nhau giữa Lincoln và Washington, Washington và Roosevelt.[197]

|

Tượng Abraham Lincoln, bên trong Khu Tưởng niệm Lincoln Tượng Abraham Lincoln, bên trong Khu Tưởng niệm Lincoln |

Lincoln sở hữu tính cách điềm tĩnh cần thiết cho một chính khách, nhất là trong tình thế phức tạp. Suốt trong năm 1862, không có ngày nào trôi qua mà không có một bài diễn thuyết kêu gọi tổng thống chấp nhận những quyết sách táo bạo nhằm chống lại nạn nô lệ và Tướng McClellan, nhưng Lincoln vẫn bất động. Ông cần phải cân nhắc cho từng bước đi để thuyết phục chính mình và giới cử tri ôn hòa ở phía Bắc rằng ông đã thử hết mọi phương cách.

Ngay cả sau khi cách chức Tướng McClellan và giải phóng nô lệ, ông vẫn kiên nhẫn chờ đợi đến thời điểm thích hợp. Sự mòn mỏi chờ đợi một chiến thắng để có thể công bố bản Tuyên ngôn Giải phóng Nô lệ có lẽ là giai đoạn nhạy cảm nhất trong nhiệm kỳ tổng thống của Lincoln. Thời kỳ chuyển tiếp là cần thiết bởi vì Lincoln biết rằng trong những lúc đất nước đang bị phân hóa nghiêm trọng thì lập trường trung dung là con đường dẫn đến thành công cho nhà lãnh đạo.

Một ngày mùa hè năm 1862, một nhóm các nhân vật tiếng tăm chủ trương bãi nô từ vùng New England đến gặp Lincoln nhằm yêu cầu ông phải chống nạn nô lệ triệt để hơn. Sau một lúc im lặng, Lincoln hỏi xem họ còn nhớ sự kiện Blondin đi dây ngang qua thác Niagara không. Dĩ nhiên là họ nhớ. Một người trong số họ thuật lại lời của Tổng thống, “Giả sử toàn bộ giá trị vật chất trên đất nước vĩ đại này của chúng ta, từ Đại Tây Dương đến Thái Bình Dương – sự giàu có, thịnh vượng, những thành quả của nó trong hiện tại và cả niềm hi vọng cho tương lai – được tập trung lại và giao cho Blondin đem chúng băng qua thác trong chuyến đi kinh khủng này;" và giả sử “bạn đang đứng trên bờ thác khi Blondin đi trên dây, khi anh đang cẩn thận dò dẫm từng bước chân và đang cố giữ thăng bằng với thanh ngang trên tay bằng kỹ năng tinh tế của mình để băng qua thác nước khổng lồ đang gầm rú bên dưới. Bạn sẽ gào thét, ‘Blondin, qua phải một bước!’ ‘Blondin, qua trái một bước!’ hay là bạn lặng lẽ đứng yên, nín thở và cầu nguyện xin Đấng Toàn Năng hướng dẫn và giúp anh ấy vượt qua cơn thử thách?”[198]

Chính là bởi vì vụ ám sát mà Lincoln được xem là vị anh hùng xả thân vì dân tộc. Trong mắt của những người chủ trương bãi nô, ông là nhà tranh đấu cho quyền tự do của con người. Đảng viên Cộng hòa liên kết tên tuổi ông với đảng của họ. Ở miền Nam, nhiều người, tuy không phải tất cả, xem ông là một tài năng kiệt xuất.[199] Kể từ sau khi Lincoln qua đời, đã có không ít tác giả viết sách về ông.[9] Cũng có nhiều mâu thuẫn giữa quan điểm của những cuốn sách viết về Lincoln.[7]

|

Thư viện và Bảo tàng Tổng thống Abraham Lincoln tạiSpringfield, Illinois Thư viện và Bảo tàng Tổng thống Abraham Lincoln tạiSpringfield, Illinois |

Theo Schwartz, cuối thế kỷ 19 thanh danh của Lincoln tiến triển chậm cho mãi đến Giai đoạn Phát triển (1900 – thập niên 1920) ông mới được xem như là một trong những vị anh hùng được tôn kính nhất trong lịch sử Hoa Kỳ, ngay cả trong vòng người dân miền Nam. Đỉnh điểm của sự trọng vọng này là vào năm 1922 khi Đài Tưởng niệm Lincoln được cung hiến tại Washington.[200] Trong thời kỳ New Deal, những người cấp tiến ca tụng Lincoln không chỉ như là người tự lập thân hoặc vị tổng thống vĩ đại trong chiến tranh, mà còn là nhà lãnh đạo quan tâm đến thường dân là những người có nhiều cống hiến cho chính nghĩa của cuộc chiến. Trong thời kỳ chiến tranh lạnh, hình ảnh của Lincoln được tôn cao như là biểu tượng của tự do, là người mang hi vọng đến cho những người bị áp bức.[201] Theo dòng lịch sử, ông đã trở thành một nhân vật tiêu biểu hàng đầu trong lịch sử nước Mỹ dân chủ, tự do.[1]

Trong thập niên 1970, Lincoln được những người có chủ trương bảo thủ trong chính trị dành cho sự ngưỡng mộ đặc biệt[202] do lập trường dân tộc, chủ trương hỗ trợ doanh nghiệp, tập chú vào nỗ lực chống nô lệ, và nhiệt tâm của ông đối với các nguyên lý của những nhà lập quốc.[203][204][205] James G. Randall nhấn mạnh đến tính bao dung và thái độ ôn hòa của Lincoln trong “sự chú tâm của ông đối với sự tăng trưởng trong trật tự, sự nghi ngờ đối với những hành vi khích động nguy hiểm, và sự miễn cưỡng của ông đối với các kế hoạch cải cách bất khả thi.” Randall đúc kết, “ông là người bảo thủ khi ông triệt để bác bỏ cái gọi là “thuyết cấp tiến” chủ trương bóc lột miền Nam, căm ghét chủ nô, thèm khát báo thù, âm mưu phe phái, và những đòi hỏi hẹp hòi muốn các định chế của miền Nam phải được thay đổi cấp tốc bởi tay người bên ngoài.” [206]

Đến cuối thập niên 1960, những người cấp tiến như sử gia Lerone Bennett, xem xét lại sự việc, đặc biệt là quan điểm của Lincoln liên quan đến các vấn đề chủng tộc.[207][208] Năm 1968, Bennett gây chấn động dư luận khi gọi Lincoln là người chủ trương người da trắng là chủng tộc thượng đẳng.[209] Ông nhận xét rằng Lincoln thích gièm pha chủng tộc, chế giễu người da đen, chống đối sự công bằng xã hội, và đề nghị gởi nô lệ được tự do sang một đất nước khác. Những người ủng hộ Lincoln như các tác gia Dirk và Cashin, phản bác rằng Lincoln còn tốt hơn hầu hết các chính trị gia thời ấy;[210] rằng ông là người đạo đức có viễn kiến đã làm hết sức mình để thăng tiến chủ nghĩa bãi nô.[211] Tác giả Thomas Krannawitter trong cuốn Vindicating Lincoln: Defending the Politics of Our Greatest President, cũng lên án các lập trường phê phán Lincoln và coi ông là một chính khách Hoa Kỳ mẫu mực, nêu lên mọi sức mạnh của nền dân chủ. Ông là hiện thân cho mọi phẩm chất cao đẹp của nền Cộng hòa.[9] Cũng giống như George Washington, ông quên mình mà chỉ lo cho dân cho nước, và biểu lộ rõ nét vĩ đại của người chính khách Hoa Kỳ thông qua tinh thần bình đẳng.[10]

Tưởng niệm

|

Khu Tưởng niệm Lincoln tại Washington, D.C. Khu Tưởng niệm Lincoln tại Washington, D.C. |

Nhiều thị trấn, thành phố, và quận hạt mang tên Lincoln,[212] trong đó có thủ phủ bang Nebraska. Tượng đài đầu tiên được dựng lên để tưởng niệm Lincoln đặt trước Tòa Thị chính Hạt Columbia năm 1868, ba năm sau khi ông bị ám sát.[213] Tên và hình ảnh của Lincoln xuất hiện tại nhiều địa điểm khác nhau như Đài Tưởng niệm Lincoln ở Washington D. C. và tượng điêu khắc Lincoln trên Núi Rushmore.[214]

Người ta cũng thiết lập những công viên lịch sử tại các địa điểm liên quan đến những giai đoạn khác nhau trong cuộc đời của Lincoln như: nơi ông chào đời (Abraham Licoln Birthplace National Historical Park) ở Hodgenville, Kentucky,[215] chỗ ông trải qua thời niên thiếu (Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial) tại Lincoln City, Indiana,[216] nơi ông trưởng thành (Lincoln’s New Salem) ở Illinois,[217] và nơi ông khởi nghiệp (Lincoln Home National Historic Site) tại Springfield, Illinois.[218][219]

|

Hình ảnh Lincoln trên Núi Rushmore. Hình ảnh Lincoln trên Núi Rushmore. |

Nhà hát Ford và tòa nhà Petersen (nơi Lincoln từ trần) được giữ lại làm viện bảo tàng, cũng như Thư viện và Bảo tàng Tổng thống Abraham Lincoln ở Springfield.[220][221] Phần mộ Lincoln trong Nghĩa trang Oak Ridge ở Springfield, Illinois, là nơi chôn cất Lincoln, vợ ông Mary cùng ba trong số bốn con trai của ông, Edward, William, và Thomas.[222]

Ngay trong năm Lincoln từ trần, hình ảnh của ông được gởi đi khắp thế giới qua những con tem bưu điện.[223] Hình ảnh của ông cũng xuất hiện trên tờ năm đô-la, và đồng xu Lincoln, đây là đồng tiền đầu tiên của Hoa Kỳ có đúc hình một nhân vật.[224]

Ngày 28 tháng 7, 1920 một pho tượng Lincoln được đặt tại một địa điểm gần Điện Westiminster, Luân Đôn.[225] Mặc dù ngày sinh của Lincoln, 12 tháng 2, chưa bao giờ được công nhận là quốc lễ, nó từng được cử hành tại 30 tiểu bang.[212] Từ năm 1971 khi Ngày Tổng thống trở thành quốc lễ, trong đó có ngày sinh của Lincoln kết hợp với ngày sinh Washington, được cử hành thay thế lễ kỷ niệm ngày sinh của ông.[226]

Abraham Lincoln

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the American president. For other uses, see Abraham Lincoln (disambiguation).

Abraham Lincoln

|

| Abraham Lincoln at age 54, 1863 |

In office

March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865

Vice President Hannibal Hamlin (1861-1865)

Andrew Johnson (1865)

Preceded by James Buchanan

Succeeded by Andrew Johnson

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

In office

March 4, 1847 – March 4, 1849

Preceded by John Henry

Succeeded by Thomas Harris

Personal details

Born February 12, 1809

Hodgenville, Kentucky, U.S.

Died April 15, 1865 (aged 56)

Petersen House, Washington, D.C., U.S.

Resting place Lincoln's Tomb, Oak Ridge Cemetery

Citizenship United States

Political party Republican (1854–1865)

National Union (1864–1865)

Other political

affiliations Whig (Before 1854)

Spouse(s) Mary Todd

Children Robert

Profession Lawyer

Military service

Service/branch Illinois Militia

Years of service 1832

Rank  Captain

Captain

Captain

Captain

Battles/wars Black Hawk War

Abraham Lincoln  i/ˈeɪbrəhæm ˈlɪŋkən/ (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. Lincoln successfully led his country through its greatest constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union while ending slavery, and promoting economic and financial modernization. Reared in a poor family on the western frontier, Lincoln was mostly self-educated, and became a country lawyer, a Whig Party leader, Illinois state legislator during the 1830s, and a one-term member of the United States House of Representatives during the 1840s.

i/ˈeɪbrəhæm ˈlɪŋkən/ (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. Lincoln successfully led his country through its greatest constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union while ending slavery, and promoting economic and financial modernization. Reared in a poor family on the western frontier, Lincoln was mostly self-educated, and became a country lawyer, a Whig Party leader, Illinois state legislator during the 1830s, and a one-term member of the United States House of Representatives during the 1840s.

i/ˈeɪbrəhæm ˈlɪŋkən/ (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. Lincoln successfully led his country through its greatest constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union while ending slavery, and promoting economic and financial modernization. Reared in a poor family on the western frontier, Lincoln was mostly self-educated, and became a country lawyer, a Whig Party leader, Illinois state legislator during the 1830s, and a one-term member of the United States House of Representatives during the 1840s.

i/ˈeɪbrəhæm ˈlɪŋkən/ (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. Lincoln successfully led his country through its greatest constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union while ending slavery, and promoting economic and financial modernization. Reared in a poor family on the western frontier, Lincoln was mostly self-educated, and became a country lawyer, a Whig Party leader, Illinois state legislator during the 1830s, and a one-term member of the United States House of Representatives during the 1840s.

After a series of debates in 1858 that gave national visibility to his opposition to the expansion of slavery, Lincoln lost a Senate race to his arch-rival,Stephen A. Douglas. Lincoln, a moderate from a swing state, secured the Republican Party nomination. With almost no support in the South, Lincoln swept the North and was elected president in 1860. His election was the signal for seven southern slave states to declare their secession from the Union and form the Confederacy. The departure of the Southerners gave Lincoln's party firm control of Congress, but no formula for compromise or reconciliation was found. Lincoln explained in his second inaugural address: "Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the Nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came."

When the North enthusiastically rallied behind the national flag after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, Lincoln concentrated on the military and political dimensions of the war effort. His goal was now to reunite the nation. As the South was in a state of insurrection, Lincoln exercised his authority to suspend habeas corpus, arresting and temporarily detaining thousands of suspected secessionists without trial. Lincoln prevented British recognition of the Confederacy by skillfully handling the Trent affair in late 1861. His efforts toward the abolition of slavery include issuing his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, encouraging the border states to outlaw slavery, and helping push through Congress the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which finally freed all the black slaves nationwide in December 1865. Lincoln closely supervised the war effort, especially the selection of top generals, including commanding general Ulysses S. Grant. Lincoln brought leaders of the major factions of his party into his cabinet and pressured them to cooperate. Under Lincoln's leadership, the Union set up a naval blockade that shut down the South's normal trade, took control of the border slave states at the start of the war, gained control of communications with gunboats on the southern river systems, and tried repeatedly to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. Each time a general failed, Lincoln substituted another until finally Grant succeeded in 1865.