Tiền nhiệm James Polk

Kế nhiệm Millard Fillmore

Đảng Whig

Sinh 24 tháng 11, 1784

Phu nhân Margaret Smith

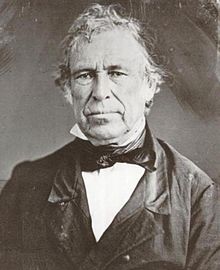

Zachary Taylor (24 tháng 11 năm 1784 - 9 tháng 7 năm 1850) là một tướng lĩnh quân sự và là tổng thống thứ 12 của Hoa Kỳ. Được biết đến với biệt danh "Old Rough and Ready", Taylor dành 40 năm sự nghiệp trong quân đội Hoa Kỳ, tham gia Chiến tranh 1812, Chiến tranh Diều hâu Đen(Black Hawk War) và Chiến tranh Seminole lần 2. Ông nổi tiếng qua các chiến thắng thời Chiến tranh Mexico-Hoa Kỳ. Là chủ nô lệ miền Nam, ông phản đối việc giải thể quyền sở hữu nô lệ tại các lãnh thổ.

Taylor không thích làm chính trị nhưng lại được đảng Whig bổ nhiệm làm ứng cử viên tranh cử tổng thống năm 1848. Trong cuộc bầu cử, Taylor đánh bại ứng cử viên Đảng Dân chủ Lewis Cass, và trở thành vị tổng thống đầu tiên của Mỹ không từng giữ bất kỳ chức vụ hành chính nào trước đó. Taylor cũng là tổng thống đầu tiên và duy nhất từ tiểu bang Louisiana, và là người miền Nam cuối cùng thắng cử tổng thống cho đến tận thời của Woodrow Wilson (Andrew Johnson trở thành tổng thống kế nhiệm).

Taylor qua đời do viêm dạ dày cấp tính năm 1850 và chỉ phục vụ được có 16 tháng trong nhiệm kỳ tổng thống. Phó tổng thống Millard Fillmore là người kế nhiệm ông.

Zachary Taylor

|

| 12th President of the United States |

In office

March 4, 1849[a] – July 9, 1850

Vice President Millard Fillmore

Preceded by James Polk

Succeeded by Millard Fillmore

Personal details

Born November 24, 1784

Barboursville, Virginia, U.S.

Died July 9, 1850 (aged 65)

Washington, D.C., U.S.

Resting place Zachary Taylor National Cemetery

Political party Whig

Spouse(s) Margaret Smith

Children Margaret Smith

Ann Mackall

Profession Major general

Religion Episcopal

Military service

Allegiance United States

Service/branch United States Army

Years of service 1808–1849

Rank Major general

Commands Army of Occupation

Battles/wars War of 1812

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was the 12th President of the United States (1849–1850) and an American military leader. Initially uninterested in politics, Taylor ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass. He was a planter and slaveholder based in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Known as "Old Rough and Ready," Taylor had a 40-year military career in the United States Army, serving in the War of 1812, the Black Hawk War, and the Second Seminole War. He achieved fame leading American troops to victory in the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Monterrey during theMexican–American War.

As president, Taylor angered many Southerners by taking a moderate stance on the issue of slavery. He urged settlers in New Mexico and California to bypass the territorial stage and draft constitutions for statehood, setting the stage for the Compromise of 1850.

Taylor died July 9, 1850, 16 months after his inauguration; the third-shortest tenure of any President.[b] He is thought to have died of gastroenteritis. President Taylor was succeeded by his Vice President, Millard Fillmore.

Taylor was the last President to own slaves while in office. He was the second of three Whig presidents, the last being Fillmore. Taylor was also the second president to die in office, preceded by William Henry Harrison who died while serving as President nine years earlier, as well as the only President elected from Louisiana.

Early life

Taylor was born on November 24, 1784, on a plantation in Barboursville, Virginia, to a prominent family of planters of English ancestry. He was the third of five surviving sons in his family (a sixth died in infancy), and had three younger sisters. His mother was Sarah Dabney (Strother) Taylor. His father, Richard Taylor, had served as a lieutenant colonel in the American Revolution.[1] Taylor was a descendant of Elder William Brewster, thePilgrim colonist leader of the Plymouth Colony, a Mayflower immigrant, and one of the signers of the Mayflower Compact; and Isaac Allerton Jr., acolonial merchant and colonel who was the son of Mayflower Pilgrim Isaac Allerton and Fear Brewster. Taylor's second cousin through that line wasJames Madison, the fourth president.[2]

Leaving exhausted lands, his family joined the westward migration out of Virginia and settled near what developed as Louisville, Kentucky on the Ohio River. Taylor grew up in a small woodland cabin before his family moved to a brick house with increased prosperity. The rapid growth of Louisville was a boon for Taylor's father, who would come to own 10,000 acres (40 km2) throughout Kentucky by the start of the 19th century; he held 26 slaves to cultivate the most developed portion of his holdings. There were no formal schools on the Kentucky frontier, and Taylor had a sporadic formal education. A schoolmaster recalled Taylor as a quick learner. His early letters show a weak grasp of spelling and grammar, and his handwriting would later be described as "that of a near illiterate".[3]

Marriage and family

Two years after being commissioned as a lieutenant in the United States Army, in May 1810 Taylor married Margaret Mackall Smith in Louisville. He purchased his first land that year in Jefferson County, Kentucky. He and Margaret had a total of six children:

Margaret Smith (c.1819-c.1820).

Sarah Knox (1814–1835), married Jefferson Davis; she died at 21 of malaria in St. Francisville, Louisiana.

Ann Mackall Taylor (1811-1875), married Robert Crooke Wood, a US Army surgeon. They had three children, including John Taylor Wood, who became a Confederate Navy officer during the Civil War, and later went to Canada.

Octavia Pannell (1816-1820).

Mary Elizabeth (1824–1909), married William Wallace Smith Bliss (died 1853); later married Philip Pendelton Dandridge

Richard (1826–1879), Army officer and Confederate general during the American Civil War.

Margaret and their children sometimes accompanied Taylor to assignments at forts under his command. At other times, they lived on the plantation in Louisville. In the 1820s, following his purchases of land in Louisiana, the family moved to establish a new home in Baton Rouge. Through the years, Taylor speculated in land and bought many slaves to develop his properties; the Deep South was becoming the cotton kingdom.

[edit]Later descendants

Richard Taylor's granddaughter, Anita Vincent Stauffer, married into the McIlhenny family of Avery Island, Louisiana, makers of Tabasco hot pepper sauce.

John Taylor Wood's great-grandsons and other descendants have had active military and police roles in Canada.

Military career

|

Zachary Taylor led the defense of Fort Harrison Zachary Taylor led the defense of Fort Harrisonnear modern Terre Haute, Indiana. |

On May 3, 1808, Taylor joined the U.S. Army, receiving a commission as a first lieutenant of the Seventh Infantry Regiment. He was among the new officers commissioned by Congress in response to the Chesapeake–Leopard Affair.[4] Taylor spent much of 1809 in the dilapidated camps of New Orleans and nearby Terre aux Boeufs.

He was promoted to captain in November 1810. His army duties were limited at this time, and he attended to his personal finances. Over the next several years, he would begin to purchase slaves and a good deal of bank stock in Louisville.[5] In July 1811 he was called to the Indiana Territory, where he assumed control of Fort Knox after the commandant fled. In only a few weeks, he was able to restore order in the garrison, for which he was lauded by Governor William Henry Harrison.[6]

During the War of 1812, Taylor successfully defended Fort Harrison in Indiana Territory from an attack by Indians under the command of the Shawneechief Tecumseh. Taylor gained recognition and received a brevet (temporary) promotion to the rank of major. Later that year he joined General Samuel Hopkins as an aide on two expeditions: the first into the Illinois Territory, and the second to the Tippecanoe battle site, where they were forced to retreat in the Battle of Wild Cat Creek.[7]

Taylor moved his growing family to Fort Knox after the violence subsided. In spring 1814, he was called back into action under Brigadier GeneralBenjamin Howard. That October he supervised the construction of Fort Johnson under his command, the last toehold of the U.S. Army in the upper Mississippi River Valley. Upon Howard's death a few weeks later, Taylor was ordered to abandon the fort and retreat to Saint Louis. Reduced to the rank of captain when the war ended in 1814, he resigned from the army. He re-entered it a year later after gaining a commission as a major.[8]

For two years, Taylor commanded Fort Howard at the Green Bay settlement. He returned to Louisville and his family. In April 1819 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel and dined with President James Monroe.[9]

In late 1821, Taylor took the 7th Infantry to Natchitoches, Louisiana, on the Red River. On the orders of General Edmund P. Gaines, they set out to locate a new post more convenient to the Sabine River frontier. By the following March, Taylor had established Fort Jesup, at the Shield's Spring site southwest of Natchitoches. That November he was transferred to Fort Robertson atBaton Rouge, where he remained until February 1824.[10]

He spent the next few years on recruiting duty. In late 1826 he was called to Washington, D.C., to work on an Army committee to consolidate and improve military organization. In the meantime he acquired his first Louisiana plantation, and decided to move with his family to Baton Rouge as their home.[10]

In May 1828 Taylor was called back to action, commanding Fort Snelling in Minnesota on the northern Mississippi River for a year, and nearby Fort Crawford for a year. After some time on furlough, when he expanded his landholdings, Taylor was promoted to colonel of the 1st Infantry Regiment in April 1832.[11]

At that time, the Black Hawk War was beginning in the West. Taylor campaigned under General Henry Atkinson to pursue and later defend against Chief Black Hawk's forces throughout the summer. The end of the war in August 1832 signaled the end of Indian resistance to U.S. expansion in the area, and the following years were relatively quiet. During this period Taylor resisted the courtship of his 17-year-old daughter Sarah Knox Taylor and Lieutenant Jefferson Davis. He respected Davis but did not approve of his daughter becoming a military wife, as he knew it was a hard life for families. Davis and Sarah Taylor married in June 1835, but she died three months later of malaria contracted on a summer visit to Davis' sister in St. Francisville, Louisiana.[12]

By 1837, the Second Seminole War was underway when Taylor was directed to Florida. He defeated the Seminole Indians in the Christmas Day Battle of Lake Okeechobee, which was among the largest U.S.–Indian battles of the nineteenth century. He was promoted to brigadier general in recognition of his success. In May 1838, Brig. Gen. Thomas Jesup stepped down and placed Taylor in command of all American troops in Florida, a position he held for two years. His reputation as a military leader was growing, and with it, he began to be known as "Old Rough and Ready."[13]

After his long-requested relief was granted, Taylor spent a comfortable year touring the nation with his family and meeting with military leaders. During this period, he began to be interested in politics, and corresponded with President William Henry Harrison. He was made commander of the Second Department of the Army's Western Division in May 1841. The sizable territory ran from the Mississippi River westward, south of the 37th parallel north. Stationed in Arkansas, Taylor enjoyed several uneventful years, spending as much time attending to his land speculation as to military matters.[14]

Mexican–American War

|

Daguerreotype of Taylor in uniform, circa 1843-5 Daguerreotype of Taylor in uniform, circa 1843-5

Main article: Mexican–American War

|

In anticipation of the annexation of the Republic of Texas, which had established independence in 1836, Taylor was sent in April 1844 to Fort Jesup in Louisiana. He was ordered to guard against any attempts by Mexico to reclaim the territory.[15] He served there until July 1845, when annexation became imminent, and President James K. Polk directed him to deploy into disputed territory in Texas, "on or near the Rio Grande" near Mexico. Taylor chose a spot at Corpus Christi, and his Army of Occupation encamped there until the following spring in anticipation of a Mexican attack.[16]

Taylor's men advanced to the Rio Grande in March 1846. Polk's attempts to negotiate with Mexico had failed, and war appeared imminent. Violence broke out several weeks later, when some of Captain Seth B. Thornton's men were attacked by Mexican forces near the river.[17] Polk, learning of the Thornton Affair, told Congress in May that a war between Mexico and the United States had begun.[18] That same month, Taylor commanded American forces at the Battle of Palo Alto and the nearby Battle of Resaca de la Palma, defeating the Mexican forces, which greatly outnumbered his own.[19]

These victories made him a popular hero, and within weeks he received a brevet promotion to major general and a formal commendation from Congress. The national press compared him to George Washington and Andrew Jackson, both generals who had ascended to the presidency, although Taylor denied any interest in running for office. "Such an idea never entered my head," he remarked in a letter, "nor is it likely to enter the head of any sane person."[20]

In September, Taylor inflicted heavy casualties upon the Mexican defenders at the Battle of Monterrey. The city of Monterrey had been considered "impregnable", but was captured in three days, forcing Mexican forces to retreat. Taylor was criticized for signing a "liberal" truce, rather than pressing for a large-scale surrender.[21] Afterwards, half of Taylor's army was ordered to join General Winfield Scott's soldiers as they besieged Veracruz. Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Annadiscovered, through an intercepted letter from Scott, that Taylor had contributed all but 6,000 of his men to the effort. His remaining force included only a few hundred regular army soldiers, and Santa Anna resolved to take advantage of the situation. Santa Anna attacked Taylor with 20,000 men at the Battle of Buena Vista in February 1847, inflicting around 600 American casualties at a cost of over 1,800 Mexican.[c] Outmatched, the Mexican forces retreated, ensuring a "far-reaching" victory for the Americans.[22] Taylor remained at Monterrey until late November 1847, when he set sail for home. While he would spend the following year in command of the Army's entire western division, his active military career was over. In December he received a hero's welcome in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, and his popular legacy set the stage for the 1848 presidential election.[23]

Election of 1848

Main article: U.S. presidential election, 1848

|

Taylor/Fillmore campaign poster Taylor/Fillmore campaign poster |

In his capacity as a career officer, Taylor had never reportedly revealed his political beliefs before 1848, nor voted before that time.[24] He thought of himself as an independent, believing in a strong and sound banking system for the country, and thought that Andrew Jackson should not have allowed the Second Bank of the United States to collapse in 1836.[24] He believed it was impractical to talk about expanding slavery into the western areas of the United States, as he concluded that neither cotton nor sugar (both were produced in great quantities as a result of slavery) could be easily grown there through a plantation economy.[24] He was also a firm nationalist, and due to his experience of seeing many people die as a result of warfare, he believed that secession was not a good way to resolve national problems.[24] Taylor, although he did not agree with their stand on protective tariffs and expensive internal improvements, aligned himself with Whig Party governing policies; the President should not be able to veto a law, unless that law was against the Constitution of the United States; that the office should not interfere with Congress, and that the power of collective decision-making, as well as the Cabinet, should be strong.[24]

|

|

Well before the American victory at Buena Vista, political clubs were formed which supported Taylor for President. His support was drawn from an unusually broad assortment of political bands, including Whigs and Democrats, Northerners and Southerners, allies and opponents of national leaders such as Henry Clay and James K. Polk. By late 1846 Taylor's opposition to a presidential run began to weaken, and it became clear that his principles more closely resembled Whig orthodoxy. Still, he maintained that he would only accept election as a national, independent figure, rather than a partisan loyalist.[25] Taylor declared, as the 1848 Whig Party convention approached, that he had always been a Whig in principle, but he did consider himself a Jeffersonian-Democrat.[24] Many southerners believed that Taylor supported slavery, and its expansion into the new territory absorbed from Mexico, and some were angered when Taylor suggested that if he were elected President he would not veto the Wilmot Proviso, which proposed against such an expansion.[24] This position did not enhance his support from activist antislavery elements in the Northern United States, as these wanted Taylor to speak out strongly in support of the Proviso, not simply fail to veto it.[24] Most abolitionists did not support Taylor, since he was a slave-owner.[24] Many southerners also knew that Taylor supported states' rights, and was opposed to protective tariffs and government spending for internal improvements.[24] The Whigs hoped that he put the federal union of the United States above all else.[24]

Taylor received the Whig nomination for President in 1848. Millard Fillmore of Cayuga County, New York was chosen as the Vice Presidential nominee. His homespun ways and his status as a war hero were political assets. Taylor defeated Lewis Cass, the Democratic candidate, and Martin Van Buren, the Free Soilcandidate. Taylor was the last Southerner to be elected president until Woodrow Wilson 64 years later in 1912.

Taylor ignored the Whig platform, as historian Michael F. Holt explains:

Taylor was equally indifferent to programs Whigs had long considered vital. Publicly, he was artfully ambiguous, refusing to answer questions about his views on banking, the tariff, and internal improvements. Privately, he was more forthright. The idea of a national bank 'is dead, and will not be revived in my time.' In the future the tariff "will be increased only for revenue"; in other words, Whig hopes of restoring the protective tariff of 1842 were vain. There would never again be surplus federal funds from public land sales to distribute to the states, and internal improvements 'will go on in spite of presidential vetoes.' In a few words, that is, Taylor pronounced an epitaph for the entire Whig economic program.[26]

Presidency

Policies

The Taylor Cabinet

OfficeNameTerm

PresidentZachary Taylor 1849–1850

Vice PresidentMillard Fillmore 1849–1850

Secretary of StateJohn M. Clayton 1849–1850

Secretary of TreasuryWilliam M. Meredith 1849–1850

Secretary of WarGeorge W. Crawford 1849–1850

Attorney GeneralReverdy Johnson 1849–1850

Postmaster GeneralJacob Collamer 1849–1850

Secretary of the NavyWilliam B. Preston 1849–1850

|

|

1849Daguerreotype by Matthew Brady.

From left to right: William B. Preston,

Thomas Ewing, John M. Clayton, Zachary Taylor,

Jacob Collamer and Reverdy Johnson, (1849)

|

Although Taylor had subscribed to Whig principles of legislative leadership, he was not inclined to be a puppet of Whig leaders inCongress. He ran his administration in the same rule-of-thumb fashion with which he had fought Native Americans.

Under Taylor's administration, the United States Department of the Interior was organized, although the legislation authorizing the Department had been approved on President Polk's last day in office. He appointed former Treasury Secretary Thomas Ewing the firstSecretary of the Interior.[27]

[edit]Slavery

The dominant issue of American politics in the 1840s was whether slavery would be permitted in the western territories of the United States. Debate between extreme pro and antislavery viewpoints had become very pronounced.[28] In 1849, Taylor advised the inhabitants of California, among whom he wanted to include the Mormons near Salt Lake City and the inhabitants of New Mexico, to establish constitutions and apply for statehood, correctly predicting that these constitutions would outlaw slavery.[28] Taylor urged Congress to admit the two states when they presented their constitutions, rather than first establishing them as territories, as he expected the latter approach would cause a debate in Congress that would revive the dangerous conflict between pro and antislavery sections of the country.[28]

Foreign affairs

Taylor and his Secretary of State, John M. Clayton, lacked experience in foreign affairs. His administration attempted to stop a filibustering expedition against Cuba, argued with France and Portugal over reparation disputes owed to the United States, supported German liberals during the revolutions of 1848, confronted Spain — which had arrested several Americans on the charge of piracy — and assisted the United Kingdom's search for a team of British explorers who had gotten lost in the Arctic.[29]

The United States met British opposition to its plans to construct a canal across Nicaragua; the British argued they held a special status in neighboring Honduras. In what has been described as Taylor's "most important foreign policy move", negotiations were held with Britain that resulted in a "landmark agreement": the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty. Both nations agreed not to claim control of any canal that might be built in Nicaragua. The treaty promoted development of an Anglo-American alliance, its completion was Taylor's last act of state.[29]

Compromise of 1850

Main article: Compromise of 1850

The slavery issue dominated Taylor's short time in office. Although a major slaveholder in Louisiana,[30] he took a moderate stance on the territorial expansion of slavery. This angered fellow Southerners. He said that, if necessary to enforce the laws, he personally would lead the Army. Persons "taken in rebellion against the Union, he would hang ... with less reluctance than he had hanged deserters and spies in Mexico."[31][32] He never wavered.

Henry Clay proposed a complex Compromise of 1850. Taylor died as it was being debated. The Clay version failed but another version passed under the new president, Millard Fillmore.

Judicial appointments

Death

|

Taylor's mausoleum at the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery Taylor's mausoleum at the Zachary Taylor National Cemeteryin Louisville, Kentucky |

The cause of Zachary Taylor's death has not been fully established.[34] On July 4, 1850, Taylor was known to have consumed copious amounts of cold milk and cherries after attending holiday celebrations and a fund-raising event at the Washington Monument.[35] (Many sources describe the event as the laying of the cornerstone, but this is wrong, as it was laid in 1848.)[36][37] Within several days, he became severely ill with an unknown digestive ailment. Doctors used popular treatments of the time. He believed he was dying, and at about 10 o'clock in the morning on July 9, Taylor called Margaret to him and asked her not to weep, saying: "I have always done my duty, I am ready to die. My only regret is for the friends I leave behind me."[citation needed] He died within the hour.[38] Contemporary reports listed the cause of death as "bilious diarrhea, or a bilious cholera".[39] Scholars believe it was a kind of severe gastroenteritis.

Taylor was interred in the Public Vault of the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. from July 13, 1850 to October 25, 1850. (It was built in 1835 to hold remains of notables until either the grave site could be prepared or transportation arranged to another city.) His body was transported to the Taylor Family plot where his parents are buried, on the old Taylor homestead plantation known as 'Springfield' in Louisville, Kentucky.

In 1883, the Commonwealth of Kentucky placed a fifty-foot monument in his honor near his grave; it is topped by a life-sized statue of Taylor. By the 1920s, the Taylor family initiated the effort to turn the Taylor burial grounds into a national cemetery. The Commonwealth of Kentucky donated two pieces of land for the project, turning the half-acre Taylor family cemetery into 16 acres (65,000 m2). On May 6, 1926, the remains of Taylor and his wife (who died in 1852) were moved to the newly constructed Taylor mausoleum nearby. (It was made of limestone with a granite base, with a marble interior.) The cemetery property has been designated as the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery.[40]

1991 study of remains

In the late 1980s, Clara Rising, a former professor at University of Florida, hypothesized that Taylor was murdered by poison. She persuaded Taylor's closest living relative, who was also thecoroner of Jefferson County, Kentucky, to order an exhumation so that his remains could be tested.[41] The remains were exhumed and transported to the Office of the Kentucky Chief Medical Examiner on June 17, 1991. Samples of hair, fingernail, and other tissues were removed, and radiological studies were conducted. The remains were returned to the cemetery and reinterred, with appropriate honors, in the mausoleum. A monolith was later constructed next to the mausoleum.

Neutron activation analysis conducted at Oak Ridge National Laboratory revealed no evidence of poisoning, as arsenic levels were too low.[42][43] The analysis concluded he had contracted "cholera morbus, or acute gastroenteritis", as Washington had open sewers, and his food or drink may have been contaminated. Any potential for recovery was overwhelmed by his doctors, who treated him with "ipecac, calomel, opium and quinine (at 40 grains a whack), and bled and blistered him too."[44]

[edit]Assassination theories

|

|

In 1978 Hamilton Smith bases his theory on the timing of drugs, the lack of confirmed cholera outbreaks, and other material.[45] Despite the 1991 forensic findings, some writers promote assassination theories; they do not represent academic consensus. Michael Parenti devoted a chapter in History as Mystery(1999) to Taylor's death, repeating a theory of the disproved arsenic poisoning.[34] Neither work has gained support.

Legacy

Because of his short tenure, Taylor is not considered to have strongly influenced the office of the Presidency, or the United States.[46] Some historians believe that Taylor was too inexperienced with politics, at a time when officials needed close ties with political operatives.[46] Despite his shortcomings, the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty affecting relations with Great Britain in Central America is "recognized as an important step in [the] scaling down [of] the nation's commitment toManifest Destiny as a policy."[46]

He was the last U.S. President to own slaves while serving in the office.[citation needed]

He was the namesake for names and places:

Camp Taylor in Kentucky and Fort Taylor in Florida.

The SS Zachary Taylor, a World War II Liberty ship, was also named in his honor.

In 1995, he was inducted into the Louisiana Political Museum and Hall of Fame in Winnfield, Louisiana, as the only U.S. President to have lived in Louisiana.

Zachary Taylor Parkway in Louisiana [47] and in Zachary Taylor Hall at Southeastern Louisiana University.[48][49]

Taylor County in Georgia

Commemoration

See also: US Presidents on US postage stamps

|

| Postage stamp, issue of 1875 |

Postage stamp, issue of 1938

Presidential dollar coin, 2009

The US Post Office released the first postage stamp issue honoring Zachary Taylor on June 21, 1875, a full 25 years after his death. In contrast, Lincoln first appeared on US postage stamps in 1866, only one year after his death while James Garfield would be honored with a postage stamp only seven months after his assassination. Sixty three years later, in 1938 Taylor would appear again on a US Postage stamp, this time on the 12-cent Presidential Issue of 1938. Taylor's last appearance (to date, 2010) on a US postage stamp occurred in 1986 when he was honored on the AMERIPEX presidential issue. After Washington, Jefferson, Jackson and Lincoln, Zachary Taylor is the fifth American President to appear on US postage. In all there are three different postage issues that have honored Taylor.[50]

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét